Location: Alpha post

Time: 23:48 Monday

Conditions: Cold and clear

Equipment: fully stocked

Dispatch

It’s been a couple of calm hours this New Year’s Eve, and you’re enjoying the peace and quiet. A handful of the expected drunk calls have gone out from other areas of town, but you’ve managed to slip through the cracks; now you’re hoping that you’ll be left alone long enough to ring in the new year. You have a little party kazoo, and even Steve the grinch has donned a party hat.

“Do you know the words to Auld Lang Syne?” you ask.

“Nobody knows the words to Auld Lang Syne.”

“I think it goes –”

The radio crackles… (click for audio)

[Ambulance 61, priority 1 to Mystic St and Beverly Rd for an MVA — Mystic St. and Beverly, that’s for a car into a tree. That’ll be in the 900 block of Mystic St. You’re responding with Ladder 1. Nearest ALS will be in the east end. Time out 11:49; A61?]

Response

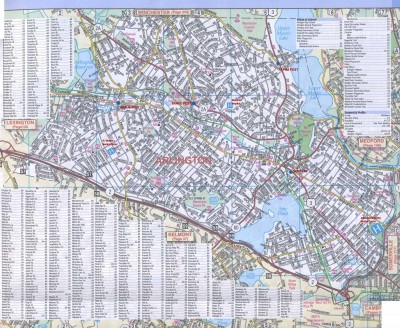

“Well gad damn,” you exclaim, tossing your kazoo onto the dash. There’s no need for the map; you know the location, which is just down the street. Ladder 1 never has a chance; you’re there in less than a minute, the first unit on scene.

Scene

You almost miss the gray sedan, even though it’s wedged against a large oak tree growing from the parking strip by the curb. That’s because its headlights are dark, although the engine is running.

A second vehicle is a dozen yards away; it’s a blue minivan, and you can see a light scrape running halfway down one side. Two teenaged females are standing outside it, and as you hop out of your truck, one waves and points at the sedan. “He just swerved and… he was swerving around the road, driving like a bat out of hell, and he swiped us, then he hit that tree!”

Damage to the sedan seems minor, with surface scratches down a few panels, and 2-3 centimeters of damage to the front fender where it’s nestled against the tree. You toss a backboard onto the stretcher, load the first-in, airway, and C-spine bags onto that, and roll over to the sedan. You ask Steve to take a look at the occupants of the minivan.

Initial Assessment

There’s only a driver inside the sedan, a 20-something male wearing a hoodie, jeans, and a thick down jacket. You open the driver’s door without difficulty. No damage is apparent to the windshield or inner compartment, although both front airbags are deployed. The driver is belted in.

“Hi,” you say in greeting, touching him on the shoulder. “I’m Sam. How’s it going?”

His eyes are open, but he doesn’t initially localize you. When you speak, he takes a few moments to sluggishly looks your way, not speaking.

“What happened, buddy?” you ask in a firm voice. Feeling for his arm, you have trouble locating a radial pulse. His skin is cool — but the weather is cold too , and the interior of the vehicle is not much warmer, as if it’s only been running for a few minutes. He is breathing, although it seems very quick, shallow and hummingbird-like.

The driver moves his mouth a little, as if trying to speak, but only manages to grunt. His head is resting against the seat, and as you watch, it falls to one side against the seatbelt. You catch a slightly fruity odor on his breath.

You kneel down, staring into the man’s face from a few inches away. “Hey!”

He makes no response. You see equal pupils that are appropriately large for the ambient light. Pinching his trapezius, you elicit a slight withdrawal and grunt.

You poke your head into the car far enough to inspect and palpate his head and neck. There are light abrasions to his face, consistent with striking the airbag; his head is otherwise intact, and his neck unremarkable. Palpating his chest, you find stable ribs.

Unzipping the bottom of the jacket, you pull up the hoodie and stop short. His abdomen is covered in blood.

A small hole is visible in the left upper quadrant, which is steadily oozing blood. The remainder of the abdomen is rock-hard.

“Oh, shit,” you remark concisely, and immediately clamp a gloved hand over the wound.

You reach up to flip on the overhead dome. With the light, you can see now that the man’s skin is paper-white. An enormous amount of blood is soaked through his shirt, pants, and pooled in the footwell beneath him.

Behind you, red lights illuminate the scene as Ladder 1 arrives. Several firefighters begin milling around nearby.

“Steve! Are they okay?” you yell to your partner, indicating the occupants of the minivan.

“Yep,” he calls back, “we’re –”

“Get over here now.”

Two firefighters are with you; one is a new guy you haven’t met, but the other is Rich Clinton, a longtime FF/EMT who works part-time with SEMS. You point to Rich. “Hey, grab some gauze, come put pressure on this.”

He recognizes your “oh shit” voice, full of tightly-restrained, consciously calm momentum. Diving into your bag, he quickly tears open a few 4x4s and takes your place. His eyes widen as he sees the blood, but he slaps the gauze onto the hole and presses down firmly.

As Steve arrives, you tell him, “We got a gunshot to the abdomen, massive bleeding. Drop the stretcher here and grab a towel, we’ll just drag him onto the board.”

Into your radio, you call, “Operations, 61.”

“61.”

“Start ALS and the captain for an unconscious GSW, plus two low-priority patients. PD as well for the crime scene.”

“61… copy. Police are en route now. ALS will be from the area of JUMC. Break. Paramedic 3 and C12, respond to Mystic St and Beverly Rd, Mystic and Beverly, just south of Alpha. A61 is on scene, came in as an MVA, A61 reporting a GSW and multiple patients.”

Steve has the stretcher at knee height with the backboard on top, and he hands you the large towel you keep in the C-spine bag (for padding and general utility purposes). Holding it by one end, you give it a couple quick swirls to spin it into a rope, then sneak around behind Rich. “I’m just gonna tow him out,” you tell him. “Keep pressure on that, don’t worry about C-spine; help out with his legs if you can.”

You wrap the towel around the neck once, then run it under both armpits, creating a kind of girdle that supports the chest. “Hold that please,” you ask the other firefighter, indicating the stretcher; he puts a foot against the wheel to brace it. Pulling at both ends of the towel as handles, you drag the patient around until his back is facing you, then haul him out of the seat with brute force, all the way onto the stretcher, not stopping until his body is entirely on the board.

“Let’s get him exposed real quick,” you say. “Rich, can you go kick our high idle and crank the heat in the back?”

Steve starts at the top and you take the bottom, cutting and ripping away clothes. His shoes come off easily, and you have a letter-opener type blade on your shears, which makes quick work of the jeans, zipping up both legs. As you reach the upper left leg and peel the material away, you find another bleeding puncture.

“Hey, we got another one here.”

It’s located in the mid-femoral area, obliquely between the front and medial faces. You find no exit wound, but the path looks to lead directly through the femur. It’s bleeding, although not quite as heavily as the abdominal wound. You press some more gauze on top. Rich has returned, so you ask him to grab the thigh cuff out of your bag.

“Let’s roll him,” Steve says. Together, you roll the patient onto one side, pulling away the now-split clothes as you do. A cloud of feathers surrounds you from the down jacket.

The exit wound from the abdominal gunshot is clearly visible, emerging from the left lumbar area several inches below the entry wound. No other trauma is notable. You grab more 4x4s and a couple abd pads, and hold the stack of gauze against the exit wound as you roll him back down; his weight maintains a reasonable amount of pressure.

“Okay, toss a couple belts on him and let’s go.” You pop up the stretcher, Rich secures the shoulder and chest straps, and you start walking for your truck. As you do, you slide the thigh cuff under the injured leg, running it all the way up into the inguinal crease; then you velcro it snugly and start pumping at the bulb until fresh blood stops rising from the wound . You tie a quick knot in both tubes.

As you’re hooking the stretcher into the back, you hear a panicked female voice from nearby. “Jamal! Jamal!”

Looking over, you see a young adult female being restrained by police. “Do you know him?” you call.

“He’s my brother! Oh, those motherfuckers. Jamal!”

“Okay, we’re taking him to University Hospital, you can look for him in the ER there. Does he have any medical conditions?”

“He… he’s got… his heart is irregular… he takes Coumadin. Is he gonna be okay?”

“I hope so. I’m sorry, we have to go.”

Steve asks, “You want me back here?”

“Uh…” But no, you need some driving magic, not a borrowed hand. “No, I need you to drive. You two, hop back here please.” You indicate Rich and the other firefighter.

You catch the attention of one of the firefighters remaining on scene, and shout, “Those two are yours, we’ll get another unit for them, okay?” They acknowledge, and you jump into the back.

An SPD officer approaches as you reach for the doors. “I need to talk to –”

“We gotta go right now, come find us at University.”

With that, the doors are shut. The heat is blasting and it’s hotter than hell. Perfect.

“Jefferson — let’s go,” you call up to Steve. “Yesterday.” With anybody else, you’d be telling them instead to take it easy, but he knows how to do that.

As he notifies dispatch you’re transporting, they advise that the P3 is 2–3 minutes away. “Want to meet the medics?” Steve asks.

“No, have them continue in for the others,” you answer. You’re not going to delay transport just for a few interventions that can wait until the ED. Steve pops into gear and starts rolling.

You sit in the tech seat while the firefighters park on the bench. You make everybody seatbelt in, then ask the younger firefighter to hold pressure on the abdominal wound (“and don’t stop”).

Meanwhile, you ask Rich to hook up the BVM and then try for a blood pressure. Then you grab the radio, raising JUMC for a priority 1 entry notification. When they reply, you take a breath, composing your thoughts — you know you’ll need to sell this one correctly — and tell them… (click for audio)

[Jefferson, Scenarioville Ambulance 61 with a level 1 trauma activation. We’re four minutes from your door, coming in BLS with a young adult male found minimally responsive after a minor MVA. Exam notes a LUQ gunshot wound, exit low back; plus second gunshot left mid-femur. No radial pulse, shallow respirations, cool and pale, rigid abdomen, now unresponsive. Reported to be taking warfarin. Jefferson, we are just a few minutes after injury, but the patient is crashing fast; we need to get into the OR very rapidly to turn this around. Activate your massive transfusion protocol and stand by for intubation and IV access; we’re going to need to reverse anticoagulation and get some blood on board, then get proceed directly to surgery. Do you copy all that?]

There’s a pregnant pause, then the hospital clicks back: “Is the patient immobilized?”

“Negative,” you answer without elaborating.

Another pause, then: “We copy, 61. We’ll be waiting. Proceed directly to Trauma 1.”

You hook the mic back onto the wall and immediately pick up the BVM. Jamal’s breathing has become so shallow that you haven’t seen any distinguishable chest movement in almost a minute. He’s not turning particularly blue, but he’s pale enough that you doubt you could tell anyway.

You stuff a couple of folded towels under Jamal’s head to approximate a sniffing position, drop in an OPA, clamp down with an EC grip, and squeeze a couple times. No good chest rise; you’re bouncing around so much that it’s tough to get a seal, and you’ve gotten some blood onto your gloves which is making them slippery.

Rich looks up from the BP cuff. “I can’t hear a thing,” he tells you. “But he’s about 60 by palp.”

“Thanks.” You immediately hand him the bag and say, “You squeeze, I’ll hold.” Then you place both hands on the mask and apply a tight jaw thrust. Rich is a little amped up, and promptly starts squeezing with both hands at about 50 times a minute.

“Take it eaaaasy,” you say. “Squeeeze one thousand… two one thousand… three one thousand… four one thousand… five one thousand… six one thousand… squeeeeze one thousand…” He settles into a more reasonable rhythm.

“Did you get a pulse?” you ask Rich.

“Like 100ish at the brachial,” he says. “Very weak.”

You bang around a few more corners. Over the radio, you hear the C12 arrive on scene and assume EMS command, then shortly after, the P3; Sneaking a look out the rear windows, you recognize the neighborhood; you’re just a minute or two out. Steve has both sirens running constantly — instead of his usual periodic bloop-bloops — and is diddling the airhorn obnoxiously at every intersection; despite intermittent traffic on the road, it’s clearing itself multiple blocks ahead of the crazy ambulance.

As you turn the corner to the hospital, you make a last check on everything. Jamal remains unresponsive to painful stimulus, and you haven’t noticed much spontaneous respiratory effort, but you’re bagging him without much difficulty, with equal chest rise. External bleeding from the abdomen has slowed but not stopped, and you can’t do much about any internal bleeding; it remains rigid and somewhat distended. Bleeding from the leg seems largely controlled. You ask Rich to check pulses, and he reports no palpable brachial, but a carotid between 100 and 120. You switch the BVM over to a portable oxygen tank on the stretcher.

Steve throws open the rear doors. A couple members of the trauma team are waiting to give you a hand. Attached to the patient by various means (holding pressure, squeezing the bag, etc.), you all disembark and start rolling briskly down the hall into one of the large trauma rooms in the high-acuity area.

A small army is awaiting you. You recognize a few faces from the ED staff, as well as Dr. Hank Pers, your SEMS medical director and one of the emergency attendings. You also recognize Dr. Ken Miles from the trauma team, a widely published luminary who’s spent the past five years leading the trauma service at JUMC into the 21st century. He’s swashbuckling and a little intense, but he has taught a number of classes for SEMS and is truly excellent. This is a room full of professionals.

They already have the bed set up, so you just line up the stretcher to slide over Jamal. As you do, a couple of the senior staff start to hush the chatter, and you raise your voice over everyone… (click for audio)

[All right, if I can have everybody’s attention for just 30 seconds please, we can get this right the first time. This is Jamal, age unknown, witnessed swerving his car around the road before crashing into a tree at low speed — restrained with airbag deployment. He has a gunshot wound in his LUQ exiting left lower lumbar, with a rigid and distended abdomen; there’s a similar gunshot in the left femur, midshaft, no exit. At least a liter or two of external blood loss on scene. There IS A TOURNIQUET at the proximal left leg, applied about six minutes ago. At the scene he was responsive to pain with a weak brachial, pressure around 60 palp, shallow respirations; he’s now unresponsive, apneic, only carotids are palpable, rate staying low 100s. Airway’s being easily managed with the BVM and OPA. No venous access. We don’t know the story here yet, but his sister reports he takes Coumadin for an “irregular heartbeat.”]

You deposit Jamal on the bed, step back, and remove the stretcher; several people descend immediately to poke and prod.

From the corner of the room, you watch with arms folded as they obtain large-bore IV access and start to pressure-infuse Vitamin K and blood products. They inspect the tourniquet and decide to leave it for the time being. Jamal is intubated quickly and easily, without the need for paralytics.

One of the residents beside you asks, “Were there any neurological deficits when he was conscious?”

“He was never really conscious,” you answer. “Grunting and withdrawing from pain when we first found him, and pretty soon totally unresponsive. We decided not to waste time boarding a dead guy.”

Dr. Miles is nodding approvingly in the background. The resident starts to mention a CT scan, but Miles shushes him. “Can you describe any finding which would not result in us opening this patient’s abdomen? No? Okay then, let’s go.” He leaves with several ducklings in tow, presumably to go scrub. In just a few more moments, the patient is prepped, and they promptly roll him out to the OR. The trauma bay looks destroyed.

Outside, Steve has parked the front tires on a curb to create a slope, and is standing in the side door hosing everything out of the patient compartment. Dr. Pers joins you. “Sam.”

“Hey doc.”

“Great work. You guys must’ve flown.” He peers into the back. “Steve, you got wings on this thing?”

“I wish.”

The doctor smiles and slips his hands into his pockets. “Hey, you know what time it is?”

You check your watch. It’s 12:02.

“Happy New Year,” he tells you.

Looking up at the starry sky, you smile. It’s actually a nice night. “Happy New Year.”

And happy new year to you, gentle reader. New scenarios start next week.

Discussion

Diagnosis: grade 5 splenic rupture; perforated diaphragm; large bowel perforation; open femoral shaft fracture

Since Dr. Pers is on staff, SEMS has a good relationship with JUMC, and he keeps you in the loop for Jamal’s follow-up. He was brought directly into the OR for exploratory laparotomy, revealing several liters of free blood and a largely destroyed spleen. He underwent damage control surgery: his spleen was removed and a large tear in the descending bowel was closed, his leg placed in traction, and his abdomen was packed with gauze and left open while he was admitted to the ICU for further stabilization. A little less than a day later, having received an impressive volume of blood products as well as tranexamic acid, he returned to the OR for more definitive repairs.

His course of recovery was complicated by numerous sequelae including significant ARDS, although JUMC follows ARDSNet recommendations for lung-protective ventilation. After aggressive but judicious ICU care, he gradually turned a corner, was transferred to a med/surg floor three weeks later, and eventually discharged with excellent long-term function.

Your quality assurance department, which reviews all trauma activations, automatically flags your run for failing to immobilize Jamal with full spinal precautions, for “overly aggressive” tourniquet use, and for consciously avoiding the ALS intercept as well as bypassing St. Vincent’s, the closer (level III) trauma center. But Dr. Pers goes to bat for you, backed vigorously by Dr. Miles. In fact, Jamal’s case was presented at JUMC’s grand rounds, and he has become a minor celebrity at the hospital. Due to the rapid transport, aggressive prehospital notification, and the actions of the trauma surgical service, you arrived at the hospital within ten minutes of the initial injury, and the patient was under the knife five minutes after that. As Dr. Miles puts it to you privately, “If almost anything had gone differently, those injuries would not have been survivable — even if he hadn’t crashed into a tree to get your attention, or you’d been just a little farther away. He was bleeding like a leaky sieve. This is the type of patient who usually dies in the first minutes after the accident [the tri-modal model of trauma mortality], but we somehow managed to juggle the balls long enough to keep him from touching the ground, and he was young enough to bounce back.” Five minutes is a hospital record, and you’re told that the surgery folks have placed a goofy plaque in their office honoring Dr. Kenneth “Five Minute” Miles.

Jamal was a member of a local gang, and had become involved in an altercation downtown where he was shot twice from around 15 feet with a 9mm handgun; he fled in his car, but quickly lost the ability to control the vehicle and hit a tree. (His spine was eventually cleared for fracture or neurological compromise.). He took warfarin (Coumadin) for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation due to a congenital condition.

After this experience, you hope that he’ll seek out a different lifestyle for himself. But that’s up to him.

This was an extremely aggressive and modern flow of care for the traumatic shock patient, and probably an unrealistic ideal in most cases; it is, however, a worthwhile goal, based on emphasizing the interventions proven beneficial, minimizing all other obstacles, and optimizing EMS to hospital interface.

Read more on BLS airway management.

Most trauma centers have two to three different levels of trauma alert, with varying names like level 1, priority 2, “stat” trauma, etc. Typically EMS will not involve itself with the specific level, but if familiar with the receiving facility’s protocols, it may help expedite the process.

Was there a reason you threw in the hint at DKA with a fruity breath during initial assessment?

Sure — he was drinking! A much more common cause of “sweetness” on the breath. (Remember, ethanol itself has no odor, but most potable spirits do.)