Location: Bravo post

Time: 10:52 Tuesday

Conditions: Misty

Equipment: fully stocked

Dispatch

Sometimes, you want to do something interesting. Sometimes you just want to nap.

Today is the latter. You’ve been piling up overtime until you’re about a day away from washing and reusing undershirts in the sink at the base, and right now, you’d give anything to just relax for a bit.

So, of course, the radio crackles.. (click for audio)

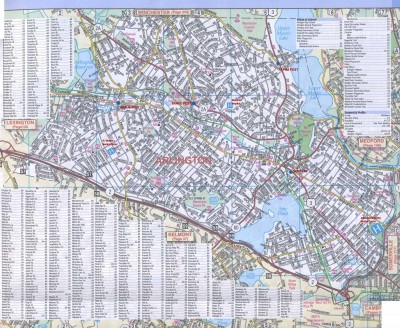

[Ambulance 61, respond priority 1 to 189 Brand St for a stroke. 1-8-9 Brand St between Finley St. and Gay St., with Engine 2. Time out 10:53. A61?]

Response

Steve acknowledges and you steer that way. Dispatch advises you that the nearest ALS will be at HQ, and asks that you update regarding your need for resources.

Stroke is an ALS dispatch according to the EMD protocol, so either dispatch was trying to hold onto their last ALS unit, or they simply hadn’t been impressed with the story. As far as you’re concerned, strokes are usually BLS anyway, and this will probably end up being toe pain.

Engine 2 is on the ball and they beat you on scene. You arrive after a four minute response to find a two-story house with the engine out front; judging by the cruiser, SPD decided to respond as well. You bring the first-in and airway bag, Steve fetches the stairchair, and you tromp up and enter the door to the first floor. You follow the sound of turnout coats to the kitchen, which is crowded with responders.

Scene

You find an elderly woman seated in a chair at the kitchen table. A middle-aged man and woman are loitering nearby.

“What’s up?” you ask nobody in particular.

The younger woman — you’re guessing daughter — chimes in. “We were eating breakfast, and my mother started to slur her speech. Her face is droopy on one side, and she hasn’t been able to walk.”

Initial Assessment

You eyeball the woman sitting in the chair. She appears alert and in no apparent distress. Approaching, you kneel beside her and say, “Hi! What’s your name?”

She looks at you. “Bernice Smythe.”

“Ms. Smythe, I’m Sam. How’s it going?”

“Okay.”

A firefighter shifts his weight. Behind you, Steve props the folded stairchair against a wall and deposits his bags on the ground.

Touching Ms. Smythe’s wrist, you feel warm, dry skin with a regular radial pulse at an unremarkable rate. Her breathing is unlabored. Nothing in her appearance strikes you as abnormal.

“Is anything bothering you?”

She shrugs. “I’m… I’m not walking very well.”

Her speech is somewhat thick and droopy, although that could be her baseline.

Peering into her face, you ask, “Can you show me your teeth? Give me a big smile.”

She gives the usual reply — “I’m wearing dentures” — but does smile. There is a subtle but noticeable asymmetry, with the right side of her face hanging lower than her left, although when she relaxes it’s not appreciable.

You take her hands, lift them until they’re at her eye level, and rotate them palms up. “All right, I want you to close your eyes, and just keep your arms right here, okay? Keep them right where they are.” She holds her arms up somewhat weakly, but equally.

Poking your fingers into her hands, you ask her to squeeze hard. Her grips seem to be equal. Then you ask her to make two fists, and “don’t let me move you” — as you attempt to flex and extend her wrists, her right side seems to be weaker in both articulations.

“Spread your fingers out like this” — you demonstrate — “and don’t let me move you.” You squeeze adjacent fingers together, and her right side seems weaker in resisting adduction.

You place your hands under her toes. “Push against me?” Her right foot seems weaker in plantarflexion. Then you switch your hands to the top of her feet. “Now lift?” Her right side is weaker in dorsiflexion as well.

“How does your head feel?” you ask Ms. Smythe.

“Fine.”

“Are you feeling dizzy at all?”

“No.”

Turning to Steve, you ask him to take a blood sugar. As he moves in, you stand and address the daughter.

“So when did this start?”

“Just a couple hours ago… we were eating breakfast.”

“What time exactly?”

“Um… about 9:30.”

You check your watch; it’s now 11:02.

“So, what? You were eating together, and you noticed this all of a sudden?”

“Yes, she started slurring her speech, and she was having trouble finding words… and you could see her face drooping. Then when she tried to walk, she couldn’t, I had to leave her in the chair. She usually walks with a walker.”

“How is she usually?”

“Well, she had a stroke last year, and she’s had a little trouble getting around since then, and she’s slow thinking of words sometimes. But nothing like this.”

“So the slurring, the droop, that’s new?”

“Yeah.”

“Is she acting normally now otherwise?”

“I guess.”

“Has it been pretty much the same since it started? Getting any better or worse?”

“Uh… about the same. I guess I was noticing the droop more when it first started.”

“How’s she been doing recently? Any other problems this morning, or over the past few days?”

“No, she’s been fine.”

“What hospital does she usually go to?”

“Memorial.”

Steve looks up at you. “138,” he reports.

You feel a familiar sense of disappointment. It’s not that you want anybody to be hypoglycemic… but usually it’s better than the alternative.

To Steve, you make a little “let’s get rolling” motion below your waist. He goes to grab the stairchair. “ALS?” he asks quietly.

You pause to think. But no — it seems unlikely that, at this point, Ms. Smythe is going to lose her airway or otherwise decompensate. Most medics would just end up idling on scene while they start an IV and attach the monitor, which will delay transport for no good reason; the best medics will just transport promptly, but you can do that yourself. “Nah.”

He props the stairchair next to Ms. Smythe’s seat, which you drag out into the middle of the room. “Ms. Smythe, we’re going to pick you up, okay? Just relax.” You take the legs, he reaches under her armpits, and you scoop her up and deposit her on the adjacent stairchair.

To a firefighter as you secure the straps: “Could one of you grab our stretcher and set it up downstairs?”

You roll to the stairs and start carrying Ms. Smythe downward. To her daughter, you ask, “Will you be coming with us?”

“Well, maybe… should I take my…”

“It would help if you came along. Do you have a list of her medications?”

“Ah… yes, hang on.”

You make it outside, where SFD has managed to figure out the stretcher; you park the stairchair alongside and repeat the lifting process. Straps go on, stretcher goes up, and shortly you’re loaded into the back of the 61.

Steve closes you in, ushers the daughter into the passenger seat, and hops into the driver side himself. “Where to?” he calls back into the patient compartment.

You think for a moment. Memorial is closest, and knows Ms. Smythe’s history, and technically speaking they’re a primary stroke center — in other words, they have a CT scanner, and a bottle of tPA somewhere. But their stroke process, or indeed their flow of care for any acute emergency, usually left a lot to be desired.

“St. V’s.”

“Gotcha.” He pops the truck into gear, and you hear him explaining the destination change to the daughter.

Wanting to get things rolling sooner rather than later, you scoot over and grab the radio. Into the cab, you call, “I’m sorry, how old is your mother?”

“Seventy five.”

“Thank you.”

You hail St. Vincent’s and deliver this entry notification (click for audio):

[St. Vincent, Scenarioville Ambulance 61. We’re five minutes from you with a stroke alert for a 75-year-old female, presenting with left-sided weakness of the upper and lower extremities, facial droop, speech slurring. Onset was witnessed at 9:30, that’s 9:30. She is euglycemic, alert, and otherwise stable. Coming in BLS, five minute ETA; any questions or concerns?]

“Negative, 61, we’ll be standing by.”

Poking your head up front, you ask, “Can I get that list from you?” She hands back a medlist, which lists

aricept

acetaminophen

Vitamin D

Miralax

Diovan HCT

aspirin

“Thanks,” you tell her. “What other medical problems has she had?”

“She had the stroke last year… her blood pressure is high… dementia, but it’s not bad.”

“Any allergies that you know about?”

“Simvastatin.”

“Any recent surgery, GI bleeds, falls, anything like that?”

“No.”

“And can I get her date of birth?

“June 7… uh, 1927.”

“Has she been to St. Vincent’s before?”

“Uh… yes, she had an orthopedics visit for her hip a year or two ago.”

Returning to the bench seat, you give Ms. Smythe a pat. “Doing okay?” She nods at you a bit vacantly. You slip a blood pressure cuff onto her arm and take a pressure of 130/84. Her pulse is steady at 80 and her respirations are unremarkable.

You take a quick moment to inspect her pupils, which appear equal and round, about 3mm in diameter. Flicking a penlight at them, they both constrict slightly. Holding the penlight so the tip of one blue glove peeks over the top, you tell her, “Keep your head where it is and follow my finger with your eyes, okay?” Holding her chin gently, you trace your finger horizontally and vertically, drawing a large H. Her eyes track it somewhat jerkily, but in a conjugate fashion without any paralysis or true nystagmus.

A quickly repeated motor exam reveals no changes. You gently pinch her forearms, asking, “Does that feel the same on both sides?” She affirms, although not very convincingly. You repeat the same process on her feet with the same result.

Pulling a nasal cannula off the shelf, you toss an oxygen tank onto the back of the stretcher and connect it at 4LPM. In a moment, you hear beeping as you enter the bay at St. Vincent’s.

As you roll through the doors, the charge nurse looks up and points to one of the trauma bays. “Number 2.” You back in and start pumping up the bed. When you look up, several figures in scrubs have filtered in.

“Everybody here?” you ask.

“Hang on,” someone replies. As if on cue, someone in a white coat turns up. “Okay.”

As you match up the beds and slide Ms. Smythe across, you address the room with this report (click for audio):

[All right, everybody, this is Ms. Bernice Smythe; she’s 75. She was eating breakfast with her daughter — gesture — at about 9:30 when she noticed her suddenly begin slurring her speech and drooping at the face, and she wasn’t able to walk. Onset was sudden and no changes since except maybe a little improvement of the droop. At this time she’s got a right-sided pronator drift, facial droop when she smiles, unilateral weakness of wrist flexion and extension, dorsiflexion and plantarflexion; peripheral sensation seems intact. Mild dementia and a stroke last year, at baseline she has mild dysnomia and difficulty ambulating but these are otherwise new findings. No recent trauma. Sugar is 138, pressure 130/84, no blood thinners except aspirin. Denies any complaints except difficulty ambulating. We’ve got her on some O2, otherwise nothing done. Followed at Memorial but she’s been seen here before.]

Nurses descend and start undressing her, fiddling with IVs, et cetera. The lady in white asks, “So time of onset was 9:30, last seen normal at… ?”

“She was normal as of last night and this morning up until a witnessed onset at 9:30. That’s her daughter there who saw it.” You indicate the daughter and they bounce a few questions off her.

You check your watch: 11:18. Not bad.

Someone from registration finds you, and you give the name and DOB. Steve pulls the stretcher into the hall and makes it up while you loiter in the corner of the room, answering a few questions as they arise and tapping at your computer. The neurologist turns up within a minute or two, and within five minutes Ms. Smythe is rolling out the door to CT. You take her daughter aside, asking if the situation has been explained to her; it has not, so you sketch out a brief description of what’s going on and what she can expect, trying to keep it general to avoid stepping on any toes.

As you’re getting ready to leave, Ms. Smythe rolls back in. You take a moment to say good-bye and wish her luck. In the hall, you pass the doc.

“What do you think?” you ask.

“Stroke for sure,” she replies. “Once we get consent we’ll start tPA.”

Out in the truck, you hop aboard. You share a quick fist-bump with Steve. “Strong work, sir. That was pretty.”

“Smoother than a baby’s ass,” he agrees as you pull out.

Discussion

Diagnosis: ischemic stroke

Stroke calls can be dispatched as anything, but occasionally they get it right. When presented with new neurological deficits such as arm drift, facial droop, or speech slurring (these three findings comprise the Cincinatti Prehospital Stroke Scale), your main job is to determine the time of onset (usually it’s not witnessed, in which case you determine the last time the patient was seen normal and when the deficits were first noticed, establishing a “window” for time-of-onset) and rule out hypoglycemia, which often causes the same deficits.

Course of care essentially involves rapid transport to an appropriate facility (usually pre-defined stroke centers), notification to mobilize the necessary resources, and any supportive care necessary. At the hospital there will be a CT scan to rule out hemorrhagic stroke, labs and other basic tests, and usually an assessment by neurology to stratify risk and determine whether administration of tPA — a clot dissolving drug — will be more beneficial than harmful. Typically tPA will only be given within the first three or four hours since onset of symptoms. Due to the critical nature of knowing the time of onset, it can help to ensure that a family member or bystander who knows the story actually rides in with you, so the hospital can confirm things with them. Factors that increase the risk of bleeding, such as recent surgery or concomitant anticoagulation (Coumadin, etc.) may be relative contraindications to thrombolysis.

With the distribution of right-sided weakness and dysphasia, this stroke was probably localized to the left side of the brain. Its findings were somewhat subtle, but consistent and widespread.

Due to the emphasis on early diagnosis, determination of appropriate destination, resource mobilization, and overall streamlined course of care, strokes are a great opportunity to practice the core skills of BLS. With that said, tPA usually has small benefits and substantial risks, so it’s not all that great. Do your thing, but in the end, view these as a practice run.

In terms of assessment, my next priorities are, in no particular order:

-Level of Consciousness

-History, especially meds, HTN, past strokes or TIAs, diabetes

-When did symptoms start, and how is she feeling now? What was the timing of everything, if known? When was she last normal prior to the onset of symptoms? Did symptoms come on suddenly or gradually?

-Any other symptoms? Headache, blurred vision, N/V/D?

-Cincinnati Stroke Scale (Facial droop, arm drift, and speech)

-BGL to rule out diabetic emergency

If we get positive findings on the Cincinnati Stroke Scale, we definitely want to transport ASAP to the closest stroke center, which is likely going to be St. Vincent’s, and get ALS only as a hookup en route (if possible) to avoid any delay in transport.

Sounds good to me, Danny. But let’s play the “what first?” game: if time is potentially of the essence, what are your true “money” questions or exam findings? What’s the most likely to change your management or decisions?

Well, if she isn’t having any stroke-like symptoms now, then I’m already thinking TIA rather than stroke, and will probably take my time (relatively speaking) and try to get as complete a history as possible to try to paint a better picture of what could be happening.

If I’m seeing signs/symptoms that make me think “STROKE!”, then I’m going to go with FAST as fast as I can, try to get a BGL, and hopefully take a family member with me to get history en route if possible.

In my opinion, in the absence of an abnormal BGL, any positive finding on the Cincinnati Stroke Scale is enough to make me substantially worried about a stroke, and at that point everything else I do is geared towards getting the patient to a stroke center as fast as possible. The rest of my assessment will be primarily focused on getting information to save time at the hospital, since there isn’t much I can do in the field to help a stroke.