Bringing order to chaos. It’s hard to suggest a more important skill for an EMT.

Emergencies are chaotic. Heck, even non-emergent “emergencies” are chaotic. The nature of working in the field is that most situations are uncontrolled. Part of our job is to bring some order to it all, sort the raw junk into categories, discard most of the detritus, and loosely mold the whole ball of wax into something the emergency department can recognize. Call us chaos translators. This is important stuff; it’s why the House of God declared, “At a cardiac arrest, the first procedure is to take your own pulse”; and it’s why we walk rather than run, and talk rather than shout.

The thing is, it’s not just those of us on the provider side that need this. Oftentimes patients need it too. Imagine: every other day of your life, you’re walking around without acute distress, in control of your situation and knowing what to expect. Today, something you didn’t anticipate and can’t understand has ambushed you — a broken leg, a stabbing chest pain — and you don’t know how to handle that. So you called 911 to make some sense of it all.

Most ailments are side effects of other problems: the fear of going mad, the anxiety of being so alone among so many, the shortness of breath that always occurs after glimpsing your own death. Calling 911 is a fast and free way to be shown an order in the world much stronger than your own disorder. Within minutes, someone will show up at your door and ask you if you need help, someone who has witnessed so many worse cases than your own and will gladly tell you this. When your angst pail is full, he’ll try and empty it. (Bringing Out the Dead)

With some patients, this is more true than with others. With some patients, there may be little to no underlying complaint; there is mainly just panic, a crashing wave of anxiety, a psychological anaphylactic reaction to a world that is suddenly too much for them. Particularly in those cases, but to a certain extent with everybody, bringing that patient to a place of calm may be exactly what they need. I have transported patients to the hospital who clearly and unequivocally were merely hoping to go somewhere that things made sense.

The burned-out medic likes to park himself behind the stretcher, zip his lip, and allow things to burn out on their own. This may sound merciless, but there is a certain wisdom to it.

We are very good in this business at escalating the level of alarm. Eight minutes after you hang up the phone, suddenly sirens are echoing down your street, heavy boots are echoing in your hall, and five burly men are crowding into your bathroom. We have wires, we have tubes, we have many, many questions. What a mess. So sometimes, once we’ve finished ratcheting everything up, it behooves us to pause, step back, and make a conscious effort to turn down the volume.

Take the stimuli of the environment, of the situation, and dial it way back. One of our best tools is to simply get the patient away from the scene — the heart of the chaos — and into the back of the ambulance, where we’re in control. It’s quiet, it’s comfortable, and there is less to look at. Move slowly, consider dimming the lights, and whenever possible avoid transporting with lights and sirens. Demonstrate calm, relaxed confidence, as if there’s truly nothing to be excited about. Some patients with drug reactions, or some developmental or psychological disorders (such as autism spectrum), may be absolutely unmanageable unless you can reduce their level of stimulation. Just put a proverbial pillow over their senses.

If you’re stuck on scene, try to filter out the environment a little. If bystanders or other responders (such as fire and police) are milling around, either clear out unnecessary personnel or at least ask them to leave the room for a bit. Make sure only one person is asking questions, and explain everything you do before you do it.

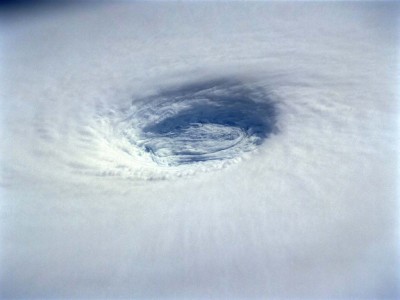

There’s a human connection here, and if you can master it, you can create an eye of calm even as sheet metal is being ripped apart around you. Look directly into your patient’s eyes, and speak to them calmly, quietly, and directly. Take their hand. Use their name, and make sure they know yours. Narrate what’s going on as it occurs, describe what they can expect next, and try to anticipate their emotional responses (surprise, fear, confusion). If they start to lose their anchor, bring them back; their world for now should consist only of themselves and you. To achieve this you need to be capable of creating a real connection; it is their focus on you that will help them to block out everything else. Done correctly, they may not want you to leave their side once you arrive at the hospital; you’re their lifeline, and it may feel like you’re abandoning them. Try to convince them that the worst is over, and they’ve arrived somewhere that’s safe, structured, and prepared to make things right. They’ve “made it.”

Applying these ideas isn’t always simple, and learning to recognize how much each patient needs the volume turned down requires experience. But just remember that no matter who they are, no matter what their complaint, most people didn’t call 911 because they wanted things more chaotic. Try to be a carrier of calm.

Recent Comments