Reader Steve Carroll passed along this recent case report from the Annals of Emergency Medicine.

It’s behind a paywall, so let’s summarize.

What happened

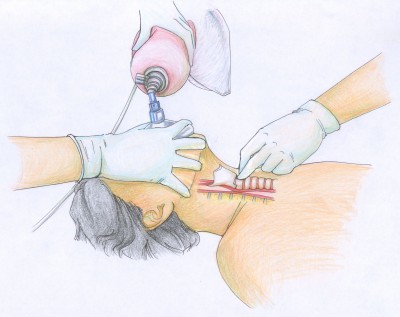

A young adult male was shot three times — right lower quadrant, left flank, and proximal right thigh. Both internal and external bleeding were severe. A physician bystander* tried to control it with direct pressure, to no avail.

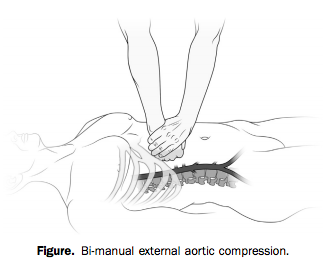

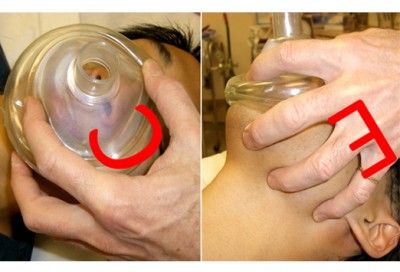

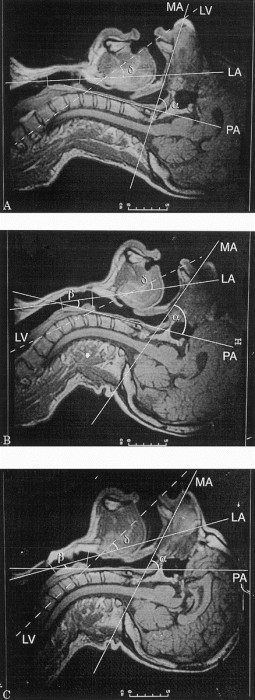

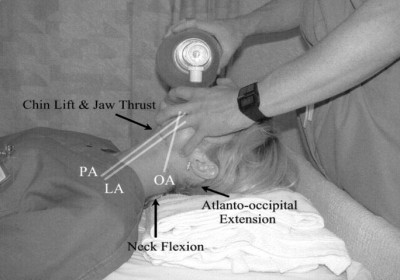

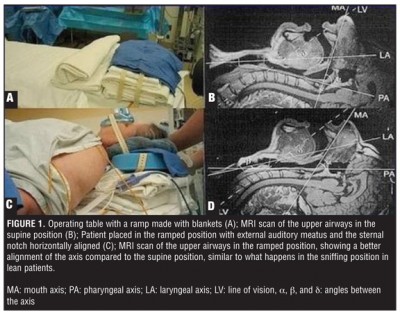

With two hands and a lot of force, however (he weighed over 200 pounds), he was able to hold continuous, direct pressure to the upper abdomen, tamponading the aorta proximal to all three wounds.

Bleeding was arrested and the patient regained consciousness as long as compression was held. The bystander tried to pass the job off to another, smaller person, who was unable to provide adequate pressure.

When the scene was secured and paramedics arrived, they took over the task of aortic compression. But every time they interrupted pressure to move him to the stretcher or into the ambulance, the patient lost consciousness again. Finally en route, “it was abandoned to obtain vital signs, intravenous access, and a cervical collar.”

The result?

Within minutes, the patient again bled externally and became unresponsive. Four minutes into the 9-minute transfer, he had a pulseless electrical activity cardiac arrest, presumed a result of severe hypovolemia. Advanced cardiac life support resuscitation was initiated and continued for the remaining 5-minute transfer to the ED.

The patient did not survive.

When the cookbook goes bad

The idea of aortic compression is fascinating, but I don’t think it’s the most important lesson to this story.

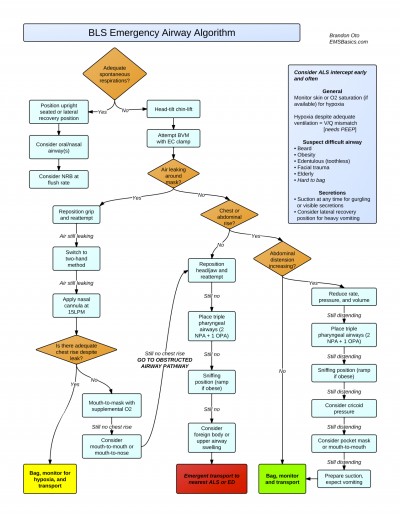

Much has been said about the drawbacks of rigidly prescriptive protocol-based practice in EMS. But one could argue that our standard teachings allow for you to defer interventions like IV access if you’re caught up preventing hemorrhage. Like they say, sometimes you never get past the ABCs.

The problem here is not necessarily the protocols or the training. It’s the culture. And it’s not just us, because you see similar behavior in the hospital and in other domains.

It’s the idea that certain things just need to be done, regardless of their appropriateness for the patient. It’s the idea that certain patients come with a checklist of actions that need to be dealt with before you arrive at the ED. Doesn’t matter when. Doesn’t matter if they matter.

It’s this reasoning: “If I deliver a trauma patient without a collar, vital signs, and two large-bore IVs, the ER is going to tear me a new one.”

In other words, if you don’t get through the checklist, that’s your fault. But if the patient dies, that’s nobody’s fault.

From the outside, this doesn’t make much sense, because it has nothing to do with the patient’s pathology and what might help them. It has everything to do with the relationship between the paramedic and the ER, or the paramedic and the CQI staff, or the paramedic and the regional medical direction.

Because we work alone out there, without anybody directly overseeing our practice, the only time our actions are judged is when we drop off the patient. Which has led many of us to prioritize the appearance of “the package.” Not the care we deliver on scene or en route. Just the way things look when we arrive.

That’s why crews have idled in ED ambulance bays trying over and over to “get the tube” before unloading. That’s why we’ve had patients walk to the ambulance, climb inside, and sit down, only to be strapped down to a board.

And that’s why we’ve let people bleed to death while we record their blood pressure and needle a vein.

It’s okay to do our ritual checklist-driven dance for the routine patients, because that’s what checklists are for; all the little things that seem like a good idea when there’s time and resources to achieve them. But there’s something deeply wrong when you turn away from something critical — something lifesaving — something that actually helps — in order to achieve some bullshit that doesn’t matter one bit.

If you stop tamponading a wound to place a cervical collar, that cervical collar killed the patient. If you stop chest compressions to intubate, that tube killed the patient. If you delay transport in penetrating trauma to find an IV, that IV killed the patient.

No, let’s be honest. If you do those things, you killed the patient.

Do what actually matters for the patient in front of you. Nobody will ever criticize you for it, and if they do, they are not someone whose criticism should bother you. The only thing that should bother you is killing people while you finish your checklist.

* Correction: the bystander who intervened was not a physician, but “MD” (Matthew Douma), the lead author, who is an RN. — Editor, 7/22/14

Recent Comments