Reader Steve Carroll passed along this recent case report from the Annals of Emergency Medicine.

It’s behind a paywall, so let’s summarize.

What happened

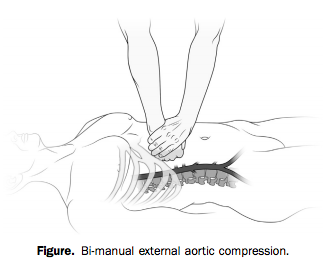

A young adult male was shot three times — right lower quadrant, left flank, and proximal right thigh. Both internal and external bleeding were severe. A physician bystander* tried to control it with direct pressure, to no avail.

With two hands and a lot of force, however (he weighed over 200 pounds), he was able to hold continuous, direct pressure to the upper abdomen, tamponading the aorta proximal to all three wounds.

Bleeding was arrested and the patient regained consciousness as long as compression was held. The bystander tried to pass the job off to another, smaller person, who was unable to provide adequate pressure.

When the scene was secured and paramedics arrived, they took over the task of aortic compression. But every time they interrupted pressure to move him to the stretcher or into the ambulance, the patient lost consciousness again. Finally en route, “it was abandoned to obtain vital signs, intravenous access, and a cervical collar.”

The result?

Within minutes, the patient again bled externally and became unresponsive. Four minutes into the 9-minute transfer, he had a pulseless electrical activity cardiac arrest, presumed a result of severe hypovolemia. Advanced cardiac life support resuscitation was initiated and continued for the remaining 5-minute transfer to the ED.

The patient did not survive.

When the cookbook goes bad

The idea of aortic compression is fascinating, but I don’t think it’s the most important lesson to this story.

Much has been said about the drawbacks of rigidly prescriptive protocol-based practice in EMS. But one could argue that our standard teachings allow for you to defer interventions like IV access if you’re caught up preventing hemorrhage. Like they say, sometimes you never get past the ABCs.

The problem here is not necessarily the protocols or the training. It’s the culture. And it’s not just us, because you see similar behavior in the hospital and in other domains.

It’s the idea that certain things just need to be done, regardless of their appropriateness for the patient. It’s the idea that certain patients come with a checklist of actions that need to be dealt with before you arrive at the ED. Doesn’t matter when. Doesn’t matter if they matter.

It’s this reasoning: “If I deliver a trauma patient without a collar, vital signs, and two large-bore IVs, the ER is going to tear me a new one.”

In other words, if you don’t get through the checklist, that’s your fault. But if the patient dies, that’s nobody’s fault.

From the outside, this doesn’t make much sense, because it has nothing to do with the patient’s pathology and what might help them. It has everything to do with the relationship between the paramedic and the ER, or the paramedic and the CQI staff, or the paramedic and the regional medical direction.

Because we work alone out there, without anybody directly overseeing our practice, the only time our actions are judged is when we drop off the patient. Which has led many of us to prioritize the appearance of “the package.” Not the care we deliver on scene or en route. Just the way things look when we arrive.

That’s why crews have idled in ED ambulance bays trying over and over to “get the tube” before unloading. That’s why we’ve had patients walk to the ambulance, climb inside, and sit down, only to be strapped down to a board.

And that’s why we’ve let people bleed to death while we record their blood pressure and needle a vein.

It’s okay to do our ritual checklist-driven dance for the routine patients, because that’s what checklists are for; all the little things that seem like a good idea when there’s time and resources to achieve them. But there’s something deeply wrong when you turn away from something critical — something lifesaving — something that actually helps — in order to achieve some bullshit that doesn’t matter one bit.

If you stop tamponading a wound to place a cervical collar, that cervical collar killed the patient. If you stop chest compressions to intubate, that tube killed the patient. If you delay transport in penetrating trauma to find an IV, that IV killed the patient.

No, let’s be honest. If you do those things, you killed the patient.

Do what actually matters for the patient in front of you. Nobody will ever criticize you for it, and if they do, they are not someone whose criticism should bother you. The only thing that should bother you is killing people while you finish your checklist.

* Correction: the bystander who intervened was not a physician, but “MD” (Matthew Douma), the lead author, who is an RN. — Editor, 7/22/14

Wow,

This article is almost a work of art, and I couldn’t agree more with each point.

The bigger issue unfortunately, is where to start within the culture to fix this issue?

Great question. Tough to answer because it’s so tied up with the other factors, such as training and actual (rather than perceived) protocol or employer mandates.

That’s why, while I push this sort of thinking, I’m also understanding when it’s not followed. Because I’m more than aware that there are many places that actually WOULD call you to the carpet for not collaring that patient (or whatever), without any irony or allowance for discussion. And the line where this ends and the grayer cultural portion begins can be a vague one; for instance, holding up your state protocol and pointing out that you’re allowed to do something won’t help if your service says, “Well, not here you’re not.”

So support from the top down is important. And conversely, of course, that’s dependent on having personnel that warrants the freedom; we all know that many rules exist to manage the bottom 1%. But the folks who lay down the law also get to decide between a system that pushes people toward this sort of “pretty package” practice or one that encourages saving lives. That decision is reflected in the protocols that are written, the way they’re enforced (petty “letter of the law” hand-slapping versus patient-oriented thinking), the people that occupy positions of authority, attitudes among ED staff, and in many other ways.

In the end, if you can create the culture you want, I think it tends to feed itself. But it’s certainly not easy.

“…So support from the top down is important. And conversely, of course, that’s dependent on having personnel that warrants the freedom; we all know that many rules exist to manage the bottom 1%…”

I do see this as a major problem, but the bigger problem, as I see it, is that we make new rules, but rarely change the culture to promote new providers being more competent and confident instead of being followers of, often, their dinosaurs and knuckle dragger mentors and FTOs. (I’m not being purposely insulting, but instead am confident that those terms bring forth some pretty specific providers to people’s minds.”

I’ve seen, and have been, a new provider who’s spent a lot of time looking at my boots around my betters, often because my better wouldn’t let me forget that they were better I was. They are too often more motivated to increase their ego than the spark a fire of a new hire or new graduate. And when they might have that desire, many are not educated in the ways of doing so.

I don’t believe that the problems that we currently face will be solved with new rules or educational standards, at least not alone. (Arguing against a common view, not what I believe to be your view) At this time we’re trying to fight a war with the majority of our soldiers afraid to load their guns, much less fire them.

Until being different, being proud of an ability to stand up and question the status quo becomes an attitude that all providers hit the streets with, I don’t really see how much can change.

Warranting the freedom will come from confidence, and confidence will come from beginning to teach those providers less confident that they are important, right out of the shoot. Not ten years from now, or after they’ve handled their first train wreck, but today. If we can make our new grads/vollies/rural providers more confident so as to be less malleable to those that came before, I think that we’ll begin to see some real change.

We need to stop demonizing free thinking. We need to stop this puppy mill culture of spitting out Medics at all cost. We need to reinstate a minimum experience level for EMTs before they can even get into medic school. We need to stop just putting butt in the seat and get back to believing that experience is a valuable asset and not just a sign that it is time to go be a nurse or a fire fighter.

Unfortunately a lot of this comes down to experience and critical thinking. You can’t teach experience, and not everyone can think critically.

Pride is also a major player, and some people just wont get past it.

BOOM!!!

Dave, you hit the nail on the head.

I have been a Paramedic for 20 years and help teach in a Paramedic program in Salem Oregon. Nothing drives me up the wall more than cookbook style Paramedicine. We are trying hard to teach critical thinking skills to the new Paramedics but it is hard.

Stopping to get an IV or…God forbid, a c-collar on this person was the nail in the coffin so to speak. Especially the c-collar. This person DOES NOT need to be placed on a board.

In fact, patients placed in full spinal immobilization in the setting of penetrating trauma had a 2.06% greater incidence of death than the ones not placed on a spine board. (EMS Spinal Precautions and the use of the Long Backboard. Prehospital Emergency Care April/June 2014)

In the same article to showed that only 1 patient in 1000 who suffered penetrating trauma had an incomplete, unstable spine. (Same citation)

Pardon my French but; Fuck the hospitals feelings. As a Paramedic you are trusted to make good decisions in the, hopefully, saving of somebodies life. Screw the “checklist” and think.

Excellent article! I have met EMS providers on both sides of that fence. I have decided for me personally a clear conscience and knowing I did everything within my power to save a life or provide the best possible care for a patient is worth everything, including losing my license! If a doc or my superiors want to take it away because I didn’t follow the cookie cutter program, then maybe I need to bein a different profession. Just one providers opinion.

What potentially hurt the patient here is actually that the EMS providers failed to follow the protocol, not that they weren’t allowed to deviate from it. Every protocol will have the ABC’s (or CAB’s) at the very top, with instructions to return to them if the patient deteriorates. In this case the external aortic compression was providing bleeding control, addressing C. When it was removed to perform procedures and the patient decompensated, the protocol would dictate a return to bleeding control, which is what went wrong here in that the EMS providers didn’t follow the protocol and do so but rather kept on going down the checklist. So what we’re seeing isn’t a failure of the cookie cutter algorithm but rather a failure to follow the algorithm due to outside influences and human factors.

You’re right. Too often we don’t reassess and reassess again as the patient’s condition changes.

Or we believe that the intervention we are attempting will do more than the action we’re currently doing.

Ive been there I’ve been cussed out at the ER for not doing more when stuck on ABCs but I always remind them if they want to come out with us to ensure we get all those other things done they are more than welcome to. I’ve yet to have anybody take me up on that offer.

Man I read this as vindication , when I got into EMS it was scoop and run,it truly was “mother Jugs &Speed), then along came training and before my eyes patients were being diagnosed to death on the street , with the advent of real trauma centers I thought the pendulum had swung back to “appropriate timely treatment” apparently not.

I recall many calls when it was ABC ABC ABC till we got to the er . This article chills me !

Sorry for the rant

I think the key is to have people with the training, experience, skill, and just plain common sense to know when to stay and pay and when to ship and run. They’re is no one answer. A proper assessment and the ability to critically think are what is needed to affect the best out come for the patient.

I have always said it is always easier to establish an IV, and obtain vitial signs while you still have them! Priorities first I don’t care about vitals if I don’t have them! Control bleeding! Get the IV enroute, O2 Nonrebreather, EKG,recruite police, fire fighters to drive so partner can assist in back! LIGHTS, SIREN BUT DRIVE AT A SPEED YOU AND YOUR PARTNER CAN FUNCTION! If code occurres enroute entubate and work! ER knows you are coming! What’s the old saying? No harm No fault! Or Hippocrates Do no harm!

I agree with everything except for have a Police Officer or Firefighter drive. They are not skilled at driving an ambulance. They drive very different emergency vehicles, neither are used to the dynamics of driving with someone working in the back. Fecal matter happens but I am the most important person in the ambulance followed closely by my partner then every other member of society finally by the patient. I am not saying that a Cop or Firefighter are not legally qualified to drive only they usually do not have enough experience driving an ambulance. Their usually priority is getting to the scene as fast as possible not driving as smoothly as you can. Any time earlier in my career I let a Cop or firefighter drive I spent more time focusing on their driving than providing patient care. I’ll take them in the back and let my partner drive.

Sometimes the patient will die. That is unfortunate, but my priority is that I make it intact to the end of my shift. I can not afford to sustain an injury. Does this mean I will not take risks? Absolutely not. I will not however let someone I do not know drive. I will forgo my seat belt in order to provide care to a patient who needs it. I would continue to tamponade the aorta. I intubate on the move and put in IVs while driving routinely. This is my job. I will also coach a police officer or firefighter in how to best help me so that my partner, arguably the most competent and skilled person on scene to drive an ambulance. Not to mention he is in the back on the next call.

So if you don’t like the way PD or FD drive your ambulance, bring it over to their station and TEACH THEM. Or, have their training officer teach them. Barring that, ask if anyone has pulled a horse trailer and was able to get the same horse back in the trailer afterwards. If they answer yes to both, they will drive your ambulance just fine. 🙂

Right on ! I’ve had fire department and police drive an ambulance for me they did fine, not an issue ,just a matter of common sense and responsibility

Most FF’s are trained and experienced in driving several apparatuses. You rotate regularly through riding on the medic, the engine, ladder etc.. If you’re a FF, you have EVOC up through the #’s and you will drive the medic (ambulance). Pretty much all EMS providers are ambulance drivers, but not everyone is a DPO (Driver/Pump Operator–the engine) so rest easy and know that you can trust a FF to drive the ambulance, but he/she will most likely provide patient care (ALS).

I just finished my course in BAA & looking forward to saving a life. In my opinion following a sequence is important,atleast you will know how to treat your patient,the ABCs are important, as for vital signs you can always check them on the way to Hospital as the patient’s life is in danger…

Hi Brandon

Really nice piece on the when the cookbook goes bad, and good commentary. Very valid points and an issue for some of our patients – a reasonable step from the case report on External Aortic Compression (EAC).

It appears that the focus of the case was on a method of hemorrhage control that is rarely taught or considered (with few exceptions such as some military services or the WHO which includes it in a checklist for severe postpartum hemorrhage and is followed by some Australian EMS). It would be a challenging to expect the EMS practitioners to employ/ continue a technique they had never heard about or seen before (and is not at all in the protocol) – rather than using direct pressure and rapid transport as per training/protocol for Junctional/Torso wounds. The standard issues of handover of care can also play a factor in some cases where the importance of a specific technique to achieve temporization can be lost in report.

A little more info can be found on EAC at

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24913094

Thanks again.

Thanks for the thoughts. I think what’s important here isn’t the specific intervention, which as you say is not exactly standard procedure in most areas. My basic point could have been made with standard direct pressure on the site of injury, or other basic therapies. If the crew here had merely held direct pressure as best they could for the duration of transport (and of course transported to the right destination with the right notification, and maybe done some basic things like preventing hypothermia), I’d have no objection even if the outcome was poor.

I’m not expecting anyone to perform TV melodramatics with every sick patient… but they should understand the goal, which approaches work toward it, and which are counterproductive.

Otherwise you’re the guy asking for their insurance information while they gasp their last breath.

My medical director, a senior trauma surgeon and surgery professor, told me almost 20 years ago: “Do whatever you have to in order to get them here with a pulse and an airway. I can’t fix dead”. That is my number one protocol/standing order/guideline.

I love that response from the surgeon.

Yea…I wouldn’t believe it for a second. As soon as something goes wrong, the medical director is going to offer you up for their own safety. There has also been precedent in NJ that if you do something you are not trained to do and beyond your scope, even with medical direction, you still lose your certs for life, so you might want to have a backup career plan.

Contrary to what is taught in EMT class, medical directors are not all powerful gods and what might amount to a slap on the wrist for them, might still end your career.

Abdominal incision with aortic clamping. Oh wait, this is not the military….my bad.

Fantastico, gracias por compartir los conocimientos

De nada!

Perhaps I’m being contrarian, but I’m going to stick up for both the paramedic and so-called “cookie-cutter” medicine.

Remember, the word “anecdote” is derived from the ancient Greek word for “cool story bro.” Let’s keep in mind that the success of the technique in this case is based solely on the perspective of ONE person, with no other documentation or corroboration. The entire discussion in the case report and here presumes that we can accept this report from the bystander at face value. We see shoddy case reports describing miraculous diagnostic and therapeutic successes all the time in journals, often based on little more than “because we said so, and it worked.” In our rush to condemn “rote” behavior, where did all our healthy skepticism go?

Now, everyone be honest here – how many times have you heard this belly-press maneuver described prior to reading the paper/FB post/Blog post? How many times have you heard your medical control – or any physician – describe it? Have you even heard of another medic ever doing this? Maybe you have, but I haven’t.

Okay, of course we want medics to “think outside of the box” when circumstances dictate. But we also want to train them to the (hopefully) evidence-based standards of the day, and monitor their performance in employing these standards. A lot of frakin’ research and consensus-building has gone into these “cookie-cutter” protocols, and you have to be pretty darn sure when and where to deviate from them.

I think we can appreciate that medics (and RNs, MDs, accountants, septic-tank repair men…) can commit serious errors of judgment when their out-of-the-box thinking morphs into “confidence-based medicine.” Heck, just this week, a paramedic self-immolated in a FB discussion after insisting that his profound insight into physiology, as well as his unique clinical “touch,” outweighed the core tenets of the cardiac arrest literature and practice standards. His actions also likely run counter to both the letter and the spirit of his EMS agency’s guidelines. Not cool, and I’d hate to be that guy when his bosses figure out what he’s been doing outside of their “box.”

So, look at this from the point of the paramedic. She pulls up to the scene, and sees a standard-issue critically injured GSW patient. A bystander, who says that they are a health care professional, is pressing with all their might (and weight) into the patient’s belly. The patient is talking and moving, but the bystander swears that this belly-press is the only thing keeping them alive. Uh-huh. Right. Should she believe the highly unusual and unverified advice of a stranger, or follow the emergency-medical and trauma guidelines that she has learned, practiced, and probably taught?

We’re criticizing her in absentia for acting entirely reasonably. And face it; you probably would have done the same thing.

Oh, for sure. I am, of course, just taking the case as described and trying to make a point. For all we know it has no resemblance to reality. Just treat it like a convenient fable.

Nor am I trying to argue for everyone doing manual aortic compression… some interesting literature and discussion has been coming up because of this topic, but it’s really beside the point.

The point is more that if you take the story at face value (and there’s obviously a narrative slant, so again, who knows what really happened), it was pretty clear what was working and what wasn’t. Push here, bleeding stops, patient wakes up. Stop and it all falls apart. If that’s what you’re seeing, the only thing you should be doing is sitting on that button until a surgeon pushes you aside, but I can imagine very many people who *wouldn’t disagree with the efficacy of the maneuver* (and in the case report, they seem on board with it), yet at some point would still stop and say, gosh, we gotta do some other things. And dat’s bad.

I think the only case reports I trust are the ones that either A) have biopsy data, or B) say “We messed up big, and here’s what happened.”

The problem is that the medic didn’t have the experience of seeing the patient wake up with the maneuver – she (paramedic K. Thrace, of course) only saw a live patient when she arrived.

In essence, she would have had to rely, not on Retrospective Trial, or a Case Report, but a {Personal communication – some dude on the street}.

Not bagging on anyone, but the below makes it sound as if they had all of the evidence necessary to continue doing what they were taught by the doc…

“…they took over the task of aortic compression. But every time they interrupted pressure to move him to the stretcher or into the ambulance, the patient lost consciousness again. Finally en route, “it was abandoned to obtain vital signs, intravenous access, and a cervical collar…”

To all: my thanks to Brooks Walsh, who pointed out an error in my write-up. The bystander was not a physician, but rather “MD,” the lead author of the paper (Matthew Douma, RN). Shouldn’t make any difference as far as the message. Sorry about that!

Wouldn’t it have made sense to take the M.D. with you to the E.d. Another set of hands in the back and someone to hold the EAC.

This was a good title, catchy even. I don’t think the “cookbook” went bad in this case. The medics following standard emergency medical guideline worked hard on a hopeless case. In the end the patient was further resuscitated in the ED with out of whack blood values (go figure) and most importantly an “inability to repair the aorta” following laparotomy.

The medics on the call likely followed the current standard of care, with at least an attempt at something (EAC) new. Make no mistake about this, external aortic compression is still experimental with very little literature to back it up at this time. Having read the article there are some very interesting points and there is opportunity to further study this maneuver in a proper ethical trial.

I do thank you for pointing out this article and situation I will be keeping an eye on this maneuver and prepare to train my staff.

It seems that many are missing the point, at least the point as I see it, that the article isn’t bagging on these medics, nor even the fact that they may have tried to fulfill their standard of care, but instead using the article to express a point that most that have been in this business for any length of time have seen, and felt over and over.

They had a conscious patient that became unconscious when an intervention was stopped. And it happened on more than one occasion. They didn’t stop the intervention (true or not, the story makes the point really well) because they believed it to be a needless or harmful intervention, but because they were (again, in theory) more than likely afraid to show up at the ER without decent dressing and vitals. Something that’s completely understandable.

I was once working a a trauma, that became an arrest enroute with a newer medic. He was in charge of the call (sort of). I’d intubated, we were managing wounds, then needed to manage the arrest after it occurred. It was of a mess. At one point he was trying to do compressions and bag at the same time while I was drawing up drugs. I said, “Brother, forget about the bag, let’s just stay with good compressions…” The bag ended up becoming dislodged and falling on the floor, I verified that my tube hadn’t moved and told him to leave it on the floor and continue compressions. A few moments later be gave up on compressions saying, “Please! Don’t make me go into the ER without the bag on the tube!”

I abandoned what I was doing to continue compressions and away we went, into the ER.

I’d tried to explain to him at the time that the compressions and ACLS were most important interventions at the moment, that the compressions would move enough air through the patent tube for our needs, that we had other priorities…but all he could think about was what the ER was going to say. He was unable to continue to evaluate his patient’s priorities in the face of what he believed were other, not pt focused priorities, though priorities that could get him fired.

I believe that that’s the point that the article was trying to make. Not that the medics were idiots, or that the protocols were stupid, but that the expectations to follow protocols, and the expectations of some, maybe many ERs, has created a culture where medics are willing to sacrifice actual care in favor of expected care whether or not it’s appropriate for their patient at the moment.

You said it better than me!

I agree completely Dwayne. When I came through paramedic class, one of my preceptor told me, “it’s all about presentation of your package!” This style of thinking us counterproductive to providing quality patient care to critical patients. Also, it seems that every time I read an EMS article, paramedics tend to get defensive in the comments. This is another problem I have seen in the EMS culture. Most tend to take new methods or new ways of thinking personally, as if someone is calling them to floor and saying they have done something wrong. We need to get out of this culture and continuously explore literature and new studies in order to continuously be able to provide a high quality of care.

A proper ethical trial for the control of life threatening hemorrhage? Not a chance… About the best you can hope for there is an animal study.

I wrote a fairly lengthy reply to this in comments on my blog post (trackback below).

But to just sum up, there are 2 major hurdles that have to be overcome to advance hemorrhage control in the field setting.

1. Is the amount of life threatening hemorrhage that is actually seen by providers. When you don’t deal with something regularly and with advanced knowledge everything looks bad. Over treatment in EMS is endemic. Especially with questionable or harmful procedures and treatments. (some examples like longboards, oxygen, and fluid therapy.)

2. There are already many forms of indirect hemorrhage control. Some, like pressure points, were removed from the tool box already. Some like MAST (specifically for hemorrhage control, not some crazy idea like redistributing blood in body compartments) and more modern versions like NAST have been lost to time.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18805742

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16516121

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9427000

Everything from chemical bandages to prefabricated tourniquets have been marketed to EMS, but education and procedures already practiced in the surgical and military environment are ignored by EMS, despite being relatively simple to perform.

If you are still trying to figure out how to save lives by hemorrhage control, you are really a day late and a dollar short. The more modern question is can you preserve quality and function?

This was the big mistake of EMS. In the effort to streamline and simplify, a considerable amount of knowledge that was once a part of EMS has been lost. Now a few decades later, everyone is trying to reinvent the wheel.

Although it is important to have a look at a checklist and get a fair idea of what to do and how, you don’t get enough time for this in most cases of accidents. And then you can’t afford to waste time when the victim is about to die in your arms.

Brandon, thank you for reviewing our case and sharing it on your blog. Great discussion here, I think all the important points have been covered eloquently by Mark, Adam, Dwayne, Jim, Domhnall and others. Also, valuable skepticism from Brook Walsh, good on you for that.

Full text here: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258102754_Temporization_of_Penetrating_Abdominal-Pelvic_Trauma_With_Manual_External_Aortic_Compression_A_Novel_Case_Report

The EMS crew that responded was excellent, truly professional. I know them from working in the city for almost ten years and I would happily have them take care of myself or my family. Unfortunately, the importance of the intervention was not effectively communicated. I could not ride with the crew because I needed to secure my residence and attend to my terrified dog.

While providing the intervention, (external aortic compression), I could barely believe what was happening. The scene was chaotic and extremely stressful, so I only realized what I had done when talking through the case with my colleague Domhnall (great comment about the role of hand-over in this case too, my friend). People often ask how I knew to provide the intervention and all I can say is that it was dumb-luck and desperation. I had been made aware of the intervention for life threatening postpartum hemorrhage (where it has demonstrated mortality benefit, see Soltan’s work) and had heard about its use during the Battle of Mogadishu. It was not a part of any of my formal training (ATLS, ITLS, PHTLS, EMT Basic etc).

I do think it belongs in trauma care guidelines for not directly compressible life-threatening junctional trauma, when no suitable alternative intervention is available and it will not delay transfer to definitive care. Junctional trauma has been identified as the leading cause of potentially survivable battlefield mortality in Eastbridge et al.’s excellent 2012 paper (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23192066). Junctional trauma often results from complex dismounted blast injury, namely IED detonations which results in multiple amputations, limbs separated from the pelvis and impossible to tourniquet. An image that stands out in my mind is one of the female victims of the Boston Marathon bombing who was bleeding to death from her groin/proximal thigh.

I like the idea of manual compression -> abdominal aortic and junctional tourniquet (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24183765) -> +/- REBOA -> operative rescue. We wrote the case up because of the though provoking discussions it seems to inspire, including unorthodox interventions, working outside existing guidelines and junctional trauma. I’m of the opinion that guidelines need to be evidence based, updated and responsibly taught. I hold the bias that guidelines result in appropriate care for the majority of patients and it is the role of the switched-on clinician to identify the minority of cases the guideline’s interventions do not apply to.

The author, commenters, skeptics and readers of this blog and others who are willing to be the voice of dissention, question dogma and change culture – are definitely part of the solution.

Matt, is there a preferred way I could contact you to further discuss this?

Hey Mike. matthewjdouma-at-gmail-dot-com is where you’ll find me. – Matt

FDA Clears a new 510(k)! The AAT is now the AAJT, the Abdominal Aortic and Junctional Tourniquet… its not just for the abdomen anymore!

The new FDA clearance provides for the following changes:

• The AAJT is now the only device to carry an indication for Pelvic bleeding, a common complication in junctional injuries as noted by the Committee on Tactical Combat Casualty Care

• The AAJT is cleared for use in the groin and axilla for 4 hours

• The hard time limit for the abdominal placement has been removed; it should be left in place until directed by a physician to be removed.

• There is no longer any contraindication for penetrating abdominal injuries.

• The AAJT has the capability to stabilize the pelvis

The AAJT remains the only junctional device to have saved human life in both upper and lower junctional bleeding. It remains the only junctional device with human research showing safety and efficacy. It is in use in almost a dozen countries around the world. It is the only junctional device with independent international validation of its effectiveness and safety. It is the only device simple enough to be applied by non-medical providers, since its application doesn’t require knowledge of the vascular anatomy. The AAJT is the only device to stay in place and effective during patient movement in confined space rescue, drags or hasty extraction.

[website redacted]

Chris Crossley

Speer Operational Technologies

Military Program Manager

Mr. Crossley,

Are you advertising on my blog?

Not the intent, but I see where that might appear.

I read this article a few days ago on Scancrit and it appeared on my FB page. I followed the thread and saw where the AAJT was mentioned in the post above mine, by Matthew. And since Junctional Devices are relatively new and unknown, I thought I would elaborate on what Matthew mentioned.

Again, my apologies, and please remove if you feel I violated the TOS.

Chris

No worries, and I understand the desire to promote a product you believe in. I also appreciate that you declared your conflict of interest up front.

To preserve the educational and non-commercial nature of this blog, though, I’ve removed the links to your site. And can you offer any literature or other evidence in support of the claims you made?

I agree with this article. Bottom line save your pt. Could you not call Medical control, ask attending Doctor to deviate from protocol and describe your pt. condition. If the Doctor is trauma trained at all he would agree with you to tx pt with press

ure only.

or taking the traumatic in extremis to the nearest dinky hospital and not a trauma center

I got fired for “deviation from protocol” for something similar. The CQI officer (who had a degree, but less than a year of actual field experience) just couldn’t wrap her head around what I did and why. And unfortunately management wouldn’t undertake any more investigation than what the CQI officer did, which was read my report. Didn’t ask my partner, or any of the other responders on scene. The patient lived, BTW, not that they cared. And it completely wrecked my life. 10 years for the company down the drain.

as a retired paramedic, there are 2 points that I take from this. 1. Just because you can do a certain tx because of your certification, doesn’t mean you have to do it.

2. there is an old saying,” a paramedic saves lives, an EMT saves paramedics. A good EMT is very good as basic skills, where a paramedic may forget the basics because they are so focused on advanced skills.

Critical skill thinking is the new way if teaching. You can’t look at a power point and expect positive results. Critical skills are just that. You teach them in a critical environment, add stressors and then you develop strong paramedics. Who cares how much they can read out of a book. Will that book save that pt? NOT. Critical thinking skills will. You have to play in your sandbox and use all your toys. Expecially your mind. And I have yet to see a book in a sandbox. Develop those critical thinking skills and then all experience to keep those skills moving forward. Stop moving people forward to fill slots on a unit. Death will find them. Seek them out. Make them weak. And ruin your service. Or do 3 hours if critical skills education a month, and make positive changes in your employees and patients lives.