There’s a secret behind this job.

You go to work. You run the calls: the boring, the exciting, the obnoxious, the weird. Occasionally, the terrible. You see, you do, you move on. Like everything else, it runs off our backs. Like rain off a tin roof.

At least, that’s what we tell ourselves. But there’s a secret.

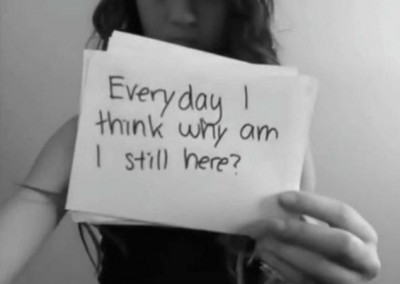

The secret is that hidden beneath the uniformed cowboy swagger of no-problem, we-got-this, no-big-deal, a thick vein of psychological stress is flowing. You don’t see it in your coworkers, because they hide it away. When it reaches you, you do the same, because it’s not okay to show it. Our professional image is unflappability, and you can’t be unflappable if you let things get to you. So we push it under the rug.

Until one of us takes their own life.

PTSD, depression, anxiety, substance abuse, and yes, suicide, are a fact of life in EMS. But we never talked about it. At least, not until a few of our colleagues were brave enough to start shining light upon the problem, in an effort called the Code Green Campaign.

Code Green collects anonymous confessions from our brothers and sisters who can’t speak them out loud, reports the (all too frequent) suicides, collates the research exploring first responder mental health, and performs outreach to build awareness.

Explore their website for more information about their basic mission. After that, come back, because I asked them to unpack a few of the subtleties behind this problem and how they’re trying to solve it.

Question: While most first responders agree with the need for the Code Green Campaign, most of us haven’t actually done anything about it. You did. How and why did it first come about? What was the impetus and how did the early days take shape?

Answer: In March of 2014 one of my co-workers died of suicide. After his death I was talking about it with a group of friends, and we realized that even though we worked for different agencies in different states, we all knew someone that had died of suicide or had a serious attempt. We knew that this couldn’t be a coincidence, so I started looking into it further. I couldn’t find a lot of data, but what I did find told me that this was a much bigger problem than anyone realized.

Once we established that there was, in fact, a mental health problem, as well as a stigma problem, we started discussing what could be done — particularly about the stigma. It occurred to us that if there was one thing first responders like doing, it is sitting around telling stories. We thought that if we could come up with a way for first responders to share the stories of their own mental health problems, other people could read them and realize they weren’t the only ones struggling. We started collecting the stories and posting them on social media every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. Things blew up from there.

In the early days things moved fast. My co-worker died on March 12th, and on March 16th we came up with the story sharing idea. We came up with our name a couple days later, and I think it was by March 23rd that we had our Facebook page up and running and stories being shared.

Q: Let’s get down to the elephant in the room. Why is this a problem for us? Why do EMS providers seem to be at higher risk for mental health issues in general, and for suicide in particular, compared to bakers, librarians, and schoolteachers?

A: I’m going to preface this answer with the warning that this is a lot of supposition, extrapolation, and educated guesswork. PTSD has most extensively been studied in the military population, so that is the best info we have. This is also a simplified answer, since the long answer would probably beat a doctoral dissertation in length.

- We are frequently exposed to known risk factors for PTSD, such as seeing people hurt or dead, feeling helplessness or fear, having poor social support after a traumatic event, and having extra stress outside of work (marital, financial, etc).

- We are poorly prepared for the realities of the job. Yes, we’re warned that we’ll see blood and guts and gore, but we’re not told that we are going to feel helpless on a regular basis, or that we’ll be scared we hurt a patient or made them worse. We’re not taught about how different this job can be from normal jobs, and how hard it can be for spouses and other family members to understand what we go through.

- Aside from stressful calls, we’re exposed to higher rates of assault, vehicle crashes, and workplace injuries than many fields, which can add to the trauma.

- We seem to have higher rates of depression, anxiety, and substance abuse, although it is unclear why.

- We work in a very macho field and we’re supposed to be the helpers, not the ones that need help. There have also been reports of people being suspended or fired after admitting they have a problem. That combination helps create a huge stigma against admitting any sort psychological problem and asking for help.

- We have more knowledge about lethal means of suicide.

Q: Okay, so let’s contrast EMS against some similar fields. Other first responders like fire and police, or medical personnel like doctors and nurses, all seem share most of the qualities you listed. Are they in the same boat? Or is there anything that puts us at greater risk compared to them?

A: Other first responders like fire and police are in the same boat. In fact, we don’t separate EMS numbers from fire service numbers because the employee base is so entwined. There are almost no fire departments out there who don’t do any EMS at all, so it is tough for us to draw a line as to who counts as EMS and who doesn’t. Just because an agency doesn’t transport doesn’t mean their employees/volunteers aren’t exposed to the same trauma. If you can’t draw the line at transport versus non-transport, where do you draw it? In the long run, it becomes almost impossible to separate people out. With police officers it is easier, but their suicide rate is on par with Fire/EMS. I believe that in 2014 there were over 140 reported police suicides.

As far as other medical professionals go, we do know that doctors do have a high rate of suicide, to the tune of 46 per every 100,000 (for first responders we’re looking at about 30 per 100,000). We don’t know what the suicide rate is for nurses, PAs, or NPs, but we wouldn’t be surprised to learn it is also high.

This is purely supposition on my part, but I do think we are particularly susceptible, because EMS is less developed than other medical fields. Nurses and doctors have well-established professional organizations representing them at the state and national levels. EMS is much more fragmented. The one big difference we’ve especially noticed with nurses and doctors compared to EMS is that many states have license preservation programs in place for RNs and physicians, but not for first responders. That is, if they have a mental health or addiction issue, their state may have an official program in place to help them keep their license while getting help. Few (if any) states have a similar program for first responders. EMS doesn’t have that kind of well-organized advocacy yet.

Q: I expect many of our readers aren’t familiar with license preservation programs. What are they and what are the possible ramifications when we lack one?

A: My answer is based on the states I’ve lived in. From what I understand, most states have such a program set up for either doctors and/or nurses. Basically, the state has recognized that nurses and doctors spend considerable time and money to obtain their licenses, and that it is in everyone’s best interest to keep them on the job, rather than automatically revoking their license. Here is an example of how it would work: say a nurse starts diverting narcotics. She self-reports her behavior to her employer and to her state licensing agency. She will likely be suspended or fired from work, but if the state has a license preservation program her license will only be suspended. The licensing board will then review the case and outline what the nurse has to do to get her license reinstated. They may require her to complete a treatment program, attend weekly counseling sessions, and submit to monthly drug tests. As long as she meets those requirements, she can keep her license.

The issue with lacking a license preservation program is that it creates an atmosphere of fear. People will avoid seeking help for anything they think could possibly cause their license to be suspended, since they have no way of knowing the outcome of that. No license means no job, and unless you want to move to another state, you’d have to come up with a new career fast.

Q: In the absence of such programs, is there a real possibility that EMS providers can lose their jobs or even their certifications merely for reporting mental health issues? In other words, no diversion or actual violations, just the typical paramedic suffering from depression, anxiety, or PTSD?

A: This question is difficult to answer because it is based on the idea that people are routinely reporting their mental health issues to the employer or the state. Unless someone is seeking to use Worker’s Comp or other employment benefits for a mental health issue, there is no reason to be reporting routine treatment to anyone (unless it is required, like with some communicable diseases). Someone wouldn’t report that they’re being treated for asthma or hypertension to their employer or state licensing board, so why would they report depression or PTSD? Employment benefit issues aside, in absence of diversion or actual violation it really doesn’t make sense for anyone but the person and their treatment team to know anything.

Such programs are generally more reactive than proactive, although in the ones I’ve looked at it is strongly encouraged to self-report issues/violations before they are caught by an employer. In fact, at my employer you’re much more protected if you self-report to the EAP than you are if you get caught.

I think that no matter what the reality is, having programs like these make it so that people don’t feel like they are backed into a corner once they develop an issue. We don’t want people feeling like a situation is hopeless, we want them to be able to see there are options.

Q: I imagine that in most cases, “reporting” occurs in the circumstances of a worker’s compensation claim (i.e. asking the employer to pay for mental health services), or perhaps when an employee needs to take time off work.

In the real world, I expect some employers are inclined to be less than supportive about these types of requests. Are they sometimes refused? Are employees sometimes asked to “prove” that their condition is work-related? Is there a legal framework mandating employers to provide these services and accommodations?

A: We answered earlier that Worker’s Comp claims or using other employment benefits are the instances an employer is most likely to learn that someone is having issues. It is difficult to answer a straight “yes” or “no” to any part of this question. No one has sat down and studied how often requests like the above are made, how often they are granted, how often they are refused, and if the response to such a request is affected by the type of employer or the state the employee is located in. We don’t know how often time off requests for mental health conditions are granted or refused, or how often they are granted or refused compared to other time off requests at that same employer. We could come up with anecdotes of both positive and negative outcomes, but there is no data.

What is and what isn’t covered by Worker’s Comp will vary from state to state and employer to employer. We do know that there are states where psychological conditions are not covered for anyone, or are only covered for certain jobs, and the employer has no control over that. It’s not uncommon for Worker’s Comp claims to be investigated no matter what kind of claim it is, so we would not be surprised if people filing a claim related to a psychological issue would be subjected to some questioning. Just ask anyone who has filed Worker’s Comp for a back injury or knee injury. Worker’s Comp tends to be difficult no matter what.

Furthermore, people who have had to take time off for physical injuries will tell you that on top of their injury being investigated and questioned, they likely also had to jump through hoops in order to return to work. Fitness for duty evaluations, physical agility tests, etc. Because of the differences between state laws and agency policies it is very difficult to know if mental health conditions are being treated differently at a significant rate.

As for accommodations, that is even more complicated. Under the Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA) employers are mandated to provide reasonable accommodations for employees that have disabilities. Now, how many first responders do you know that are willing go through that process, and then admit to their employer that they have a disability that needs to be accommodated? Additionally, first responder agencies are in a tough spot when it comes to accommodations because this field is so unpredictable. Agencies can’t ensure that you’ll never run another pediatric cardiac arrest, or never have to respond to a certain address again. If someone has an anxiety attack while responding to a call, or on scene of a call, is taking them out of service going to be considered reasonable? Probably not. Accommodations get very complicated very quickly.

Q: Interesting. So despite these challenges, the problem is clearly an urgent one. What steps can field staff take to prevent and manage mental health issues, whether for themselves or for their colleagues?

A: Resiliency, and building resiliency factors, seems to be a key to helping prevent mental health issues from arising, so everyone should review what resiliency factors they have and work on building upon them. People also need to be able to recognize signs of decline in themselves, such as worsening sleep, increased drinking, and anger issues. For co-workers, the biggest thing is not to be afraid to say something to someone if you think there is a problem. Asking someone, “Are you thinking of suicide?” is not going to put the idea into their head — so if you’re concerned, ask.

Something else that is important is reducing the stigma around mental health in general. Don’t make jokes about “BS psych patients” or complain that psych calls are a waste of time. This contributes to the stigma and makes it harder for people to admit they have their own problem.

Q: What other points do you want do make on this important topic?

A: We need to keep talking about this and keep the conversation going. Changing how mental health is addressed is going to involve changing the culture, which is going to take time and effort.

For people who want to get involved there are several things you can do. Speak up if you hear someone speaking negatively about mental health, whether in the context of our peers or our patients. If you hear about a suicide, please report it to either Code Green or to the Firefighter Behavioral Health Alliance. All reports are confidential and we do not disclose information without permission.

If you know of a first responder–friendly mental health professional in your area, let us know so we can add them to our resource database. It may not seem like much, but this kind of stuff is incredibly helpful to us and to the cause.

Visit the website of the Code Green Campaign to learn more, read personal accounts, and see else what you can do to help.

Recent Comments