The Internet is a wonderful educational resource.

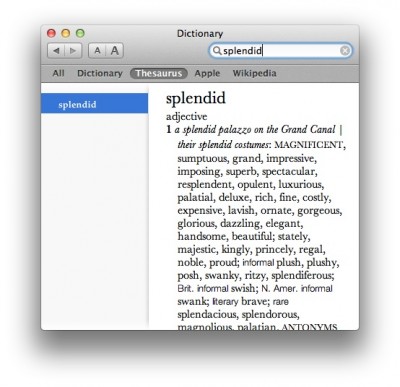

I hope this doesn’t come as a surprise to anybody, but it’s good to be reminded. As little as 20 years ago, it simply wasn’t possible to learn things in the same way or to the same extent as today, because you had to seek out the information like Indiana Jones hunting a lost jewel-encrusted kumquat. Now there are a thousand PhD’s worth of knowledge available for anyone with a modem (although it behooves us to remember that much of it is still more easily found offline, and some remains completely undigitized even now).

I have always relied heavily upon this resource, and the majority of the synapses currently rattling around my noggin wouldn’t be there if it weren’t for the ’net. I went to school, sure, but when it came to pursuing my interests and hobbies, that’s not where the money was. It even filled the bowl of my early work history — I worked in web design, various sectors of freelance writing, even as a certified locksmith, all of it made possible by self-education via an endless tap of bits and bytes.

When I first became involved in EMS, I expected that to remain true. But it wasn’t.

EMS 2.0: Good, bad, and ugly

Although somewhat inchoate in my early days, the EMS 2.0 movement was already getting legs, and was driven by an online community of paramedical luminaries hoping to remodel our damaged field into a modern, functioning system.

More recently, the larger arena of the medical community — with emergency medicine leading the way — has embraced FOAM, the general principle of free online medical knowledge-sharing. This is good stuff, and it’s just what we need.

But when I was a green EMT — and we all know how unprepared a freshly certified newbie can be — I turned to the web in the hopes it would help me learn, improve, and become better at my job. To some extent, it did. But I was also stymied.

Everywhere I turned I found veteran EMTs and paramedics advocating for increased education and training within our field. They seemed to passionately believe in making prehospital providers become better clinicians. Yet whenever I would ask medical questions to try and do exactly that — become better — I wouldn’t get answers. I would get further diatribes about the shortcomings of EMS education. Or suggestions to read a textbook (only rarely was one recommended). Or, if I pressed the point, the advice to go to paramedic or even medical school, because this sort of inquiry was likely to make me a fish out of water in my current profession.

Truth be told, I rarely got any answers where I didn’t dig them up myself. And I found this strange. Why would people purportedly so interested in advancing their profession seem to have so little motivation to actually do it?

Time has passed, and I have more perspective. In retrospect, the folks on the other end of the screen often didn’t know the answers to the questions I was asking, or only knew the answers in an incomplete or experiential way. Time has also brought along some actual progress, and there are more true FOAM resources out there.

Yet in the prehospital world, noisemaking still seems to predominate over knowledgemaking. For every blog post, website, forum thread, or social media group dedicated to transmitting information, there are ten whose primary occupation is posting long, repetitive screeds about the gaps in EMS education and the sorry state of our profession.

Now, everybody has a life outside of the internet (well, most everybody), and some of these people are indeed practicing what they preach. They’re teaching and precepting, writing and organizing, even lobbying to accomplish the changes we all dream of achieving.

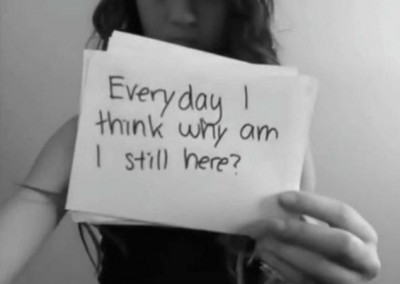

Many others, though, seem to have endless time and energy for complaining about how dumb everyone else is, and very little for correcting that dumbness. More disturbingly, in recent times, the tone of these complaints has taken a strange turn toward arrogance. Novices foolish enough to poke out their heads are decried for not being up to the level of the complainer (interestingly, the level of the complainer is usually presumed to be the appropriate one — nothing more and nothing less). I imagine a great deal of this stems from frustration. But it certainly doesn’t contribute to a solution, nor does it speak very highly of the veterans behind the keyboards, who are missing the opportunity both to educate and to model professionalism. (Hint: there is no degree of expertise that ever makes arrogance appropriate.)

Yes, ideally we will move to a place where everybody staffing an ambulance has a strong initial education in anatomy, physiology, pathology, and medicine. Yes, this will probably entail degree-granting programs and a fundamental paradigm shift from our current model of training. But until then, there are thousands of EMTs and paramedics on the road or in the classroom with a grossly limited knowledge-base, and a significant number of them are motivated to do better than that. Are you going to blow them off until the day of rapture, or are you going to try and help?

I didn’t want to write this post, because I didn’t want to be part of the problem. This site aims to be zero percent complaining and 100% educating. But we’re just a drop in the bucket, because there are a lot of smart people out there who could do far more good than a hundred EMS Basics, and I wish they would remember it.

Recent Comments