Mostly, people get into healthcare because they want to help people. And there’s no bigger and better way to help than saving lives.

Of course, that’s not really a cool thing to talk about, and we’re nothing if not cool, so most new folks clam up about lifesaving pretty quick. Then before long they’ve transitioned all the way to full-on Nicholas Cage burnout mode and managed to forget about that heroic stuff completely. To quote Dr. Saul Rosenberg: “I think the current generation of young people are terrific…. so much smarter, and so much broader, and so much more altruistic. At least until they come to medical school.”

But the fact is that there’s something very basic and very noble about the simple act of saving a life. To help shine light back on that deed rather than on the more ignoble parts of the job we do, I’d like to talk about some notable lifesavers throughout the years. Maybe we can learn a few things from them. Or maybe, at least, we’ll be reminded about the things we used to admire.

Today, let’s talk about…

The Royal Humane Society

In London in 1774, there were a whole lot of people drowning.

It wasn’t hard to understand. Most folks couldn’t swim, and many lived and worked on or near the water, especially the Thames river that flows through the city. Shipping and other water-based commerce was common, along with recreational activities like ice skating (sometimes on thin ice). To make a long story short, death by drowning was a frequent occurrence.

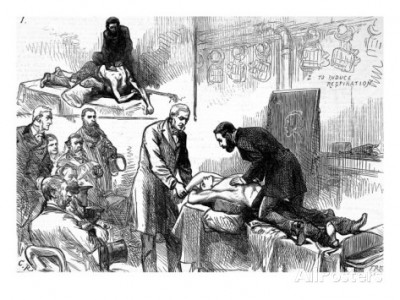

The science of resuscitation was in its infancy, and little was known about what could be done to bring back near-drowning victims. There were some interesting new ideas, but even if they were effective, there wasn’t much opportunity to use them — victims were usually presumed already dead and therefore beyond help.

(Any of this sound familiar? The problem of bystander intervention remains the toughest part of saving lives even today.)

William Hawes and Thomas Cogan were a couple of English physicians who believed that, with the current techniques and their best efforts, some of the drowned victims might be saved. (Hawes had, in fact, been paying out rewards to anyone who brought him recently-drowned bodies still “fresh” enough to be revived.) They thought that medicine could do better. So with some friends and colleagues, they sat down and founded the elegantly named Society for the Recovery of Persons Apparently Drowned, a sort of club with the goal of saving Britons from drowning.

The Society gave out cash rewards to anyone who attempted a rescue, more if they succeeded, and even awarded money to homeowners and publicans who allowed victims to be treated in their buildings. People being people, this quickly led to two-man scams where a “rescuer” and a “victim” would stage a drowning, then split the reward. So monetary prizes were soon discarded, except in rare cases, in lieu of certificates recognizing the lifesavers.

Gradually, the Society (after a few years switching to the the shorter name) began setting up stations and “receiving houses” near the water, where volunteers stored equipment and launched rescues. They were undoubtedly responsible for popularizing the concept of resuscitating the near-dead, and were among of the first to develop any type of rescue service for civilian medical emergencies. Kinda like the grand-daddy of EMS. In their literature, the Society asked:

Suppose but one in ten restored, what man would think the designs of the society unimportant, were himself, his relation, or his friend — that one?

The Society still exists, and has shifted from solely recognizing water rescues to acknowledging all manner of lifesaving heroism using a range of different medals and certificates. Awardees have included Alexander the First and author Bram Stoker.

Read through some of the most recent winners. They’re all good yarns. Humane Societies (not to be confused with the folks who protect animals) now exist in many countries of British descent, such as Australia and Canada, as well as other regions (including my own state of Massachusetts).

If you are honored by the Royal Humane Society, you’ll receive a medal stamped with their emblem: a fat cherub holding a sputtering torch, blowing at it with puffed cheeks, doing his best to fan a dying flame. Across the top:

lateat scintillula forsans

“A small spark may, perhaps, lie hidden.”

Recent Comments