Anybody who’s spent time in medicine (and it doesn’t take long, because nowadays this is often covered in initial training) has heard two contradictory lessons:

- Good caregivers must demonstrate empathy and compassion for the suffering of their patients.

- Good caregiver must not become too close or attached to their patients.

The reasoning behind both truisms is simple enough. If you don’t care about your patients, you can’t practice good medicine, because that requires caring about what’s ailing them and wanting to do something to help. On the other hand, if you become entangled in the suffering of everybody who sits down on your stretcher, you will die a thousand times in the course of your career. That’s too much tragedy for anyone to bear.

So, you should care, but not too much. We’ve all known providers who don’t care. They’re bad. Bad at medicine, bad people, they don’t like their jobs and patients don’t like them. We’ve all known providers who cared too much, too. They’re good at their jobs, for about six months, then they flame out and quit. See how long you last when you have an extended family of hundreds, it grows each shift, and they’re all dying.

You can find your own strategy to walking this tightrope. Experienced, durable providers seem to become skilled at connecting with their patients, but compartmentalizing it appropriately, so that when things go badly, it doesn’t hit them too hard. You do your best, they survive or they don’t, and you move on to the next patient. It’s not your emergency.

This is probably the right approach. However, I’ve always found it a little bit distasteful. Click here to watch a clip from House that helps demonstrate why.

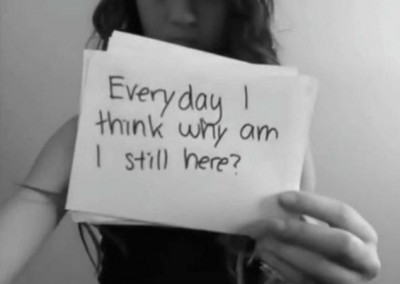

“When a good person dies, there should be an impact on the world. Somebody should notice. Somebody should be upset.”

Doesn’t that seem right?

A human being, with a lifetime of living behind them, has disappeared forever. There’s no life that isn’t complex enough and full enough and astonishing enough that we couldn’t put it up on a pedestal and watch it for days and discuss it and applaud it and munch popcorn while savoring all the decisions and revisions that we didn’t make, but which are awfully familiar. Even the mistakes aren’t usually so alien that we don’t recognize a little bit of ourselves in them.

When a person like that — and they’re all like that — drops off the face of the world, it should raise an alarm. People should put down their newspapers and look up. It should be a big goddamned deal. There are billions of human on the planet, and they’re all going to die eventually, many in the hands of medical providers, some of them in yours. But the numbers don’t change the fact that for the person who died, their life was their whole life. There should be grief.

Maybe it’s better when there’s family and friends and others to care. If a passing leaves a room full of loved ones in tears, maybe that makes it easier to walk away, knowing the job of mourning is well in hand. No silent snuffing of a candle here; the loss was recognized. That’s not very rational, but it’s how it feels to me. When somebody dies and nobody seems to know, or care, it seems like your duty to give a crap.

Isn’t it an insult to blow it off? When you were chatting with that patient and building your rapport and connecting as fellow people, would you have told them, “Listen, there’s something you should know. We’re getting along now, and we’re friends, and I want the best for you, and I’d fight for it too. We can laugh together or shake hands or hug. If you walk out of here, maybe we’ll even maintain a relationship. But if you die, I’m going to document it, wash my hands, and walk away like you’re just another number. Hope that’s okay.”

Isn’t that a little two-faced and deceptive — like acting friendly to someone, then badmouthing them as soon as they leave? How can you behave both ways and see both as compatible?

I don’t know, and maybe it’s not our job to be professional mourners. Maybe it’s not our job to mark each person’s passing. But in some sense, if we truly care about our patients, it seems like it is, and that’s quite a burden to add to our responsibilities.

What do you think?

Recent Comments