One more post about glucometry is pending, but for now, something lighter.

Decades of medical interns have been raised on the Laws of the House of God. The House of God was a cynical and dark look into the world of modern medicine, and its “Laws” were about as uplifting as condensed soup, but they rang true enough that you’ll still hear them quoted in the halls of medicine today (including those of the real-life “House of God,” where I find myself more shifts than not).

In any case, laws come in handy. Although I’m a believer in the nuanced and detailed analysis, as I age and my neurons gradually turn to cotton candy, I increasingly see the value in basic rules of thumb to guide us through the tangled web of life, and especially of this job.

A good law is simple. It’s always true, or almost always, and the exceptions prove the rule. It’s not specific to a certain region or company, but is something you can keep under your hat and carry with you throughout your career. It’s clear and it say something fundamental about the kind of provider you want to be. But most of all, a good law is not just an empty platitude, but rather an actionable guide-post that can answer real questions in real situations. When times are hard or temptations loom, it’ll tell you what to do.

With no further ado, then, here are mine. I believe in them, I follow them, and like good unguent, I wholeheartedly prescribe them for universal application. I am not wise, but whenever I do a good job of faking it, it’s by following these principles.

THE LAWS OF EMS

- Help your patient in any way you can.

- Be nice to everybody. It’s your job.

- If you can’t save their life, make their day a little better.

- Protect your partner.

- Have a reason for everything you do.

- Leave the patient better off than when they met you.

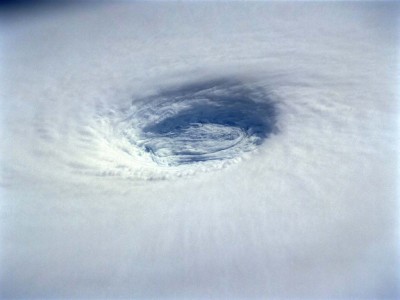

- It should get calmer when you show up.

- Good habits make doing the right thing easy.

- Tomorrow, nothing will remain but your documentation.

- Everything’s a bigger deal to the person on the stretcher.

But that’s just me. What laws do you believe in?

Editor’s note: this post was expanded into a feature piece for EMS World Magazine in the March 2014 issue.

Recent Comments