“He always said if there was any way he could help someone, he would.”

Carolyn Delaney

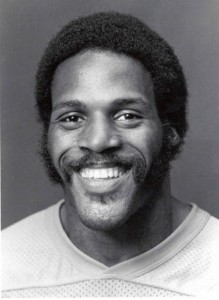

Not too many people know about Joe Delaney anymore.

He was a running back. Played for the Kansas City Chiefs, just a couple seasons — 1981 and ’82. Played high school and college ball before that, and ran track too. He was very good.

Delaney looked like he’d make a real mark in the NFL, but his career was short, and nowadays he’s been mostly forgotten. Sure, he held some long-standing records, but who hasn’t?

His claim to fame was something different.

One day in the summer of ’83, at a park in Monroe, Louisiana, three young children waded out too far into an artificial pond, floundered, and began to drown. Delaney, nearby, heard their cries for help. Although unable to swim, he immediately dove into the water to attempt a rescue.

The situation was chaotic, stories differ, and any definitive account of the events has been lost over the years. Whatever happened, the aftermath found Delaney drowned alongside two of the children; the third had made it to safety. One of the victims had eventually been rescued, but died at the hospital; the other was recovered by divers, DOA, along with Delaney himself.

This is an EMS website, and I’m not retelling this story as a teachable moment. As public safety professionals, we instinctively turn up our lip at Delaney’s actions. “Noble, but foolish,” we quip; becoming a victim, or a martyr, is no help to anyone. Perhaps the American Red Cross tells this same story in its lifeguarding courses to illustrate the importance of safe rescue methods. I’m certainly not recommending diving into pools if you can’t swim, or running into burning buildings without protection, or jumping out of planes without a parachute. This isn’t about heroism.

I want to use Joe Delaney’s example to illustrate something else.

“People ask me, ‘How could Joe have gone in that water the way he did?’ And I answer, ‘Why, he never gave it a second thought, because helping people was a conditioned reflex to Joe Delaney.’ ” (Sports Illustrated, 1)

He was fast, and he could handle a ball, but those weren’t the kind of stories people told about this rookie running back. Instead, they talked about how he “… mowed this woman’s lawn in the dead of Louisiana summer…” “… gave this person money to get through a bad stretch…” “… turned this child away from drugs…” And how every time, he did these things without question, without hesitation. Merely out of a basic, instinctive drive to help people.

Our job as EMTs is to stabilize. Treat and transport. Provide field assessment and triage. Activate appropriate resources. It’s medicine, or it’s public safety. Or something.

There’s a lot of somethings, and I’m not sure if I can remember them all the next time the tones drop. For sure I don’t think we’re getting paid enough to do ten different jobs.

But then there’s Joe Delaney.

“He always said if there was any way he could help someone, he would.”

Just that. If there was a way — any way — that he could help another human being, he would. That was only criterion. Simplicity itself.

What if that was the attitude we adopted? What if that was the job of the EMT?

The nice thing about wanting to help is that it’s pretty simple. When that’s all you want, you don’t need much more.

Joe Delaney was known for his thriftiness, for living simply even after going pro.

“Don’t you want nothing for yourself?” Carolyn would ask Joe.

“Nah,” he’d say. “You just take care of you and the girls.” (Sports Illustrated, 2)

And it’s funny. But when you view your job as helping your patients, in any way you can, a lot of other stuff seems to fall by the wayside. Is transporting this sort of patient your business? Do you really need to fluff this pillow? I don’t know; does it help? If it does, does anything else matter?

Naturally, there are things to consider. Because typically, the way we can help is through clinical intervention, through skilled medical assessment and treatment. If we helped in another way, they’d call us something else, like “plumbers” or “dentists.” And if we’re better at our craft, we can help more. That’s why we open the books and palpate the rubber mannekins. Because we recognize that if Joe did know how to swim, more lives might have been saved that day.

But the technical aspect is a means to an end, and just one means of many.

If you ask around the base, and people are truly honest, many will admit they got into this job at least partly from a desire to help people. It’s an organic urge, and a good one, and it brings us to the table, but then the years and the worries and the details of how and why and but… start to muddy the waters, and at some point we find ourselves forgetting that basic passion. Striving towards other goals. Elevating the details. And sometimes that’s okay.

But the next time we roll up those garage doors, maybe we can think back, and remember what matters. Maybe we can take a page from Joe Delaney, and every day assert this simple promise: if there’s any way we can help someone, we will.

Recent Comments