Location: Alpha post

Time: 10:31 Wednesday

Conditions: Warm and clear

Equipment: fully stocked except one backboard, one no-neck collar, one pair headblocks, one icepack

Dispatch

You’re parked under a shady tree, and Steve is snoozing while you play with your smartphone. Another day in paradise.

You’re just starting to reflect that it’s been a fairly quiet Wednesday morning when the radio crackles…

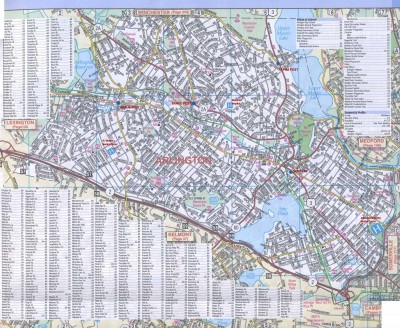

[Ambulance 61, 322 Stowecroft Road — 3-2-2 Stowecroft Road for an unknown medical. 322 Stowecroft is between Ridge St and Columbia Rd. You’re responding with Engine 2. A61?]

Response

Steve jerks awake with the tone and immediately pops the truck into gear.

“Unknown medical,” you remark. “I see that the EMD system is as rigorously-applied and fruitful as always.”

Clearing his throat, your partner answers, “Isn’t that the new girl on the horn?”

“Uh… Xena? Zirbella? Yeah, that’s her.”

“Shaleigh, I think.”

“Kinda nice to hear, the radio’s been such a sausagefest lately.”

He squirts around traffic with ease. You’re expecting to beat the engine — you’re closer than their station — but they must’ve been on the road, because you hear them call off shortly before you arrive. It’s a small shopping center, four or five stores around a parking lot, and you see the engine parked there in front of a 7-11.

Steve pulls to the curb, and you hop out. Tossing the first-in and oxygen bags onto the stretcher, you roll inside together.

Scene

It’s a typical convenience store, and the engine company is loitering around with what looks like an employee and a couple bystanders. On the ground is a young adult female, appearing generally well, supine with her eyes open. One of the firefighters is holding her head, and a few candybars and snacks litter the ground nearby, as if somebody fell.

Nobody offers anything, so you park the stretcher and ask, “What’s up?”

The cashier says, “She was standing in line and she suddenly fell down and started shaking.”

“Ah… okay. Does anybody know her?”

Everyone shakes their heads.

Initial Assessment

You kneel down. She looks to be in her 20s, perhaps even college-aged, with no obvious injury or lesions. You can see her chest rising with her breathing, somewhat irregular but deep and adequate, and when you take her wrist, you feel a strong, regular radial pulse at an unremarkable rate. Her skin is pink, warm, and dry.

Her eyes are open, and she’s staring upward, not moving. You can see that her pupils are midsized and equal. Leaning forward into her field of vision, you say, “Hi!” She doesn’t localize or acknowledge you.

You firmly pinch her trapezius, digging your thumb into the nerve, and shouting “Hey!” No answer. A few moments later, she does move her left arm aimlessly, letting it rise and then drop back onto her stomach.

To Steve, you ask, “Grab a pressure?” As he moves in, you retrieve the glucometer and start setting up for a finger-stick.

“Ya want this?” one of the firefighters says, holding up their pulse oximeter.

“Uh, sure.” They love that thing.

Your patient grunts and tries to roll over. You gently keep her from getting too far. To the cashier, you say, “So she walked in here to buy something?”

“Yes, I suppose, she was standing in line… with that soda.” He points to a Diet Coke on the ground.

“Acting normal? Did anything seem wrong?”

“No, she seemed fine. Well… I think she did hold his head, like it hurt or something.”

“Okay, and then what?”

“She just suddenly got stiff and fell down like a log, boom, and she lie there shaking.”

“Shaking? With her whole body? Both arms and legs?”

“Uh… yes I think so.”

“How long was she down there?”

“Oh, five minutes? She stopped right before the fire truck got here.”

You’ve wiped a fingertip with alcohol, pricked her with a lancet, and milked out a drop of blood. Sucking it into the tip of the test strip, the meter beeps at you: 91.

Steve pulls his scope out of his ears. “152/90,” he reports.

You nod. The firefighter has stuck on the sat probe, and looking down, you read a HR of 99 and a sat of 97% off the screen, with a nicely bouncing waveform.

Clicking your radio, you hail Operations, but hear only static. You try again and get the same, only a few garbled syllables making it through. Jeez, you’re not exactly inside the hall of the mountain king; but then, radio reception is often sketchy in this part of the city, for reasons beyond you.

Patting your pockets, you find the Nextel instead. Extracting the ruggedized phone, you punch the first speed dial, which plugs you through to the direct line for your dispatcher.

“Ooooperations,” she answers.

“Howdy, Sam on the 61. Uh… not sure if you had any ALS rolling this way, but you can cancel ’em if so.”

“Okay, I gotcha. I had someone in the area.”

“Thanks.” You hang up.

The patient is turning her head back and forth, starting to look around; the firefighter tries to control her head with some difficulty. You lean in and call at her again, but she’s still not answering.

“See if she’s got an ID or anything,” you ask Steve. While he digs, you do a quick physical exam. There’s a decent bump on the back left of the head, without any bleeding. Pupils are midsize, and you flick a light into them, inducing relatively brisk constriction. There’s no other apparent trauma to the head or neck.

Her lungs are clear to auscultation bilaterally, abdomen is soft without any abnormality, and her ribs, pelvis, and extremities are grossly stable and atraumatic. There are no lesions, needle tracks, Marks of Cain, or anything else striking or noteworthy.

Rocking back on your heels, you look over to Steve, who seems to have found a wallet in the little purse. He reads off, “Bridget Starr, 5/29/80… so, she’s 23. Scenarioville address. Ah… student ID here for Jefferson U Medical School.”

“Okey doke. Let’s get her boarded, folks.”

Steve tucks the cards away. One of the firefighters has already helpfully retrieved a board and your C-spine bag, so you grab an adult collar, lean over to eyeball her neck, and adjust it to the no-neck size. While you velcro it around, Steve slides a longboard alongside.

“Shall we roll? Okay, your count. One, two, three” — you logroll her onto the board, and you briefly examine her back, finding nothing exciting — “and down, one, two, three.”

Straps go on, someone drops the stretcher alongside, and you lift Bridget using the board. Once she’s situated Steve starts taping her head to some blocks. You take a moment to rifle through her purse a bit more. Other than a little bottle of Aleve, there are no other meds, or anything interesting except makeup. You do find her iPhone in a little pink case, and you’re starting to poke through it, looking for someone who might know something useful, when you hear: “Sam!”

Turning, you see that they’ve got Bridget neatly packaged. “Where are we going?” Steve asks. He points at fire, indicating that they want to know.

You ponder. Although someone might know her at JUMC, the medical school is administratively different from the hospital, so it’s not like she’s going to pop up in their system. Plus she’d probably find it a little awkward to poop where she eats, so to speak. There’s no real reason to think she’s high risk, so you figure anywhere’s okay.

“I guess Memorial.” You point with your thumb; you can actually see the hospital (their cooling tower at least) from the window.

They load up the stretcher and you hop in behind. As you park yourself on the bench, you see Bridget looking around purposefully from her strapped-down position. You lean into her line of sight.

“Bridget? Hi.”

She localizes you and says, a little slowly but coherently: “Hi. What…”

“You’re in an ambulance. We found you in the 7-11 on Stowecroft, it sounds like you had a little seizure. Okay?”

Staring at you, she seems to understand, but in the same way you’d understand if someone said you were growing little tentacles on your back. “A… seizure?”

“That’s what it sounds like. Have you ever had a seizure before?”

“No… never…”

“Okay. We’re just going to roll you over to the hospital and they’ll check you out. I apologize for all this stuff; it’s all just precautionary in case you hurt your neck or your back when you fell. So no need to worry, just lay back and relax, hopefully we’ll get you off this board in a few minutes, and they’ll try and figure out what happened and why.”

She seems to be following you about three-quarters, like someone who’s “not drunk, just drinking.” You dial it back to something simpler. “Is Memorial Hospital okay? Is there another hospital you usually use?”

“No… I don’t… I’ve never been in a hospital.”

Looking up, you see Steve sitting in the driver’s seat. Catching his eye in the rear view mirror, you give him a thumb’s up — “Memorial! Nice steady 2.” He nods and starts rolling.

To Bridget: “I’m Sam, by the way. It’s Bridget, right? Bridget Starr?”

She tries to nod in the collar.

“How are you feeling now?”

“Okay… confused.”

“That’s normal. Are you having any pain?”

“No… well… this thing is kinda hurting my neck.”

You smile sympathetically. “I know, I’m sorry. Like I said, we’ll get it off as soon as we can. They may want to do an x-ray or something similar at the hospital first. Nothing else is hurting you? How about your head?”

“No… my head’s okay”

“How’s your chest feel?”

“Fine.”

“And your breathing?”

“Okay.”

“Any palpitations in your chest, dizziness, nausea, weakness?”

“No.”

“Numbness or tingling in your hands or your feet?”

“No.”

You let her squeeze your hands, dorsiflex and plantarflex her feet, and find equal and normal strength all around. Pinching at the backs of her hands and behind her knees, she notes equal sensation bilaterally.

“Great, great. Any medical problems?”

“No…

“Do you take medication for anything?”

“No… uh… I take birth control.” There’s a pause, as if neurons are clicking on sequentially. “Reclipsen.”

“Okay. What do you remember about what happened?”

“Just… standing in line… then the next thing I knew I was here.” Pause. “Tonic clonic seizure?”

Med student. Right. “That’s what it sounds like. You were post ictal for a few minutes there. How have you been feeling recently? This morning? Past few days? Any issues?”

“I’ve been feeling all right.”

“I’ve gotta ask — do you normally drink every day?”

“No!” she assures you. There’s a little amused lilt to her voice; she’s clearly perking back up. “Maybe once or twice a week. Socially.”

“Stress relief?” you smile. “You’re a student over at Jefferson Med, right?”

“I am. Second year.”

You realize you’re getting distracted, and scoot over to grab the radio. Hailing Memorial, you ask while waiting for them to come on the line, “Take your boards yet?”

“Not yet, I’ve been studying.”

The hospital signs on, and you ramble off this notification… (click for audio)

[Memorial, Scenarioville Ambulance 61; we have a 23-year-old female, had a tonic clonic seizure and fell, struck her head. Sugar’s normal, vitals okay, she’s coming around now, we’ve got her on a board. We’re just down the road, we’ll see you shortly; questions?]

They respond with an incoherent but perfunctory blurp which you presume to be dismissive. You hang the mic.

“Any drugs or alcohol today, Bridget? Recreational, anything?”

“No, just my pill.” She smiles.

“So, 23-year-old female with new onset of an uncomplicated tonic clonic seizure. No prodrome or preceeding symptoms, no significant history. Vitals, blood sugar, physical exam unremarkable. What’s your diagnosis?”

She stares off. “Herpes encephalitis.”

Silence. You cock an eyebrow at her. From outside, you hear beeping as Steve backs the truck.

“Or Taenia solium cysticercosis,” she muses at the ceiling.

You snort with laughter and pat her on the shoulder. “I think you had it the first time. Definitely the herp.”

She giggles as Steve pulls out the stretcher. Inside, you’re waved into a room, and you lift her over to a bed on her backboard. As you raise the rails and adjust a blanket over Bridget, a nurse wanders in with a scrap of paper and nods at you. You give her this report… (click for audio)

[Hallo. This is Bridget, 23, no history, a healthy med student over at Jefferson. She was standing in line at a 7-11 when she was witnessed to suddenly go stiff, fall, bump her head, and start shaking with her whole body. A good few minutes in duration, terminated spontaneously, she was post-ictal for at least six, seven minutes, gradually started to come around, pretty much 100% now. Got a lump on the back of her head, no other apparent injury, no other pain or complaints, no recent issues, no meds or drugs or alcohol, normal neuro exam. Basically in good shape, but no history of seizures, so… sugar’s 91, pressure about 150/90.]

She thanks you. You let Bridget know that you’ll be back, head out to register her and grab a demographic sheet, and peck away at your report for a bit. When you wander back in, she’s off the board, still wearing the collar.

Approaching, you lean on the rail and say, “Okay, we’re going to boogie. Can I get you another blanket?”

“No, I’m good,” she smiles back. “Thank you.”

“Thanks yourself. Good luck with the herps.”

“You too.”

She signs for you, and you head outside with the board and straps. Steve helps you pack everything back up.

“A nice young lady,” you comment as you roll up straps.

“Probably gonna be your boss one day,” Steve answers.

Discussion

Diagnosis: idiopathic tonic-clonic seizure

The first goal on seizure calls should be differentiating them from other, similar syndromes. Syncope can look like a seizure and can be caused by practically anything, so keep a wide net — even cardiac arrest is often confused with seizure (due to sudden collapse, unusual breathing, and sometimes vomiting or incontinence). But remember: seizures themselves can range from mild tics or automatisms (simple partial seizures) to brief periods of non-obvious unresponsiveness (absence seizures) to full-body rigidity and shaking (generalized tonic-clonic seizures). For all seizures when a history is not known, ask “why” — hypoglycemia is a common cause, alcohol withdrawal should be considered, and trauma or stroke should be ruled-out, among others.

If still seizing on your arival, it’s an ALS call; although most seizures self-terminate, if they last long enough to persist until EMS arrives at the patient side, you’re usually in the realm of probable status epilepticus, which needs to be pharmacologically terminated (the medics will give a benzo).

If it’s stopped prior to your arrival, expect a post-ictal period (after generalized seizures) where the patient may be profoundly confused, non-verbal, or even combative. C-spine should be considered as well, unless the patient was witnessed without a fall or potential injury.

Our patient above, with a first-time seizure and no other history, will be worked up for acute causes, and if there are no findings, followed up as an outpatient for recurrence. If additional episodes occur, she will likely be diagnosed with epilepsy and managed with medication.

Scary situation. Seems like status epilepticus? Firefighter holding cspine so we’re thinking possible unknown head trauma. I’d start on vitals, administer o2 via nrb, package her up. Load and go to closest hospital. If vitals are unremarkable id still take them every 3-5 minutes.

My thoughts would remain on epileptic like seizures that were reported and possible drug use. Rapid physical exam and removing nail polish would probably remove drugs from my mind. Id also be interested to know if pupils were responsive.

I don’t know the rules regarding rummaging through pt.s purse but it would help ID her and it may have Rx clues. Same for cell phones with “dad” contact.

Good thoughts! Some counter-thoughts:

1. If seizure is on the menu, C-spine is usually wise to consider, since people who suddenly seize often fall, don’t protect themselves, and (most importantly) are hard to assess for injury afterwards.

2. What’s the typical course for a seizure? What would we expect to see before, during, and after?

3. Rules on rummaging: usually, “go for it.” Sometimes caution is wise so you don’t grab a needle or whatnot, but detective-work is always a good idea, especially for these (fortunately somewhat rare) obtunded patients without anyone accompanying them.

1. Totally agree. I wasn’t really thinking about how the blocks and board would hinder my ability to do an assessment .

2. Before: if pt is epileptic they may have tells such as halo effect with colors or sounds or smells. These effects seem to be undocumented in pt.s suffering febrile, septic, diabetic, traumatic and drug related seizures.

2. During : convulsions, incontinence , abnormal posturing (decorticate, decerebrate), quick oxygen depletion.

2. After: postical state(where our pt. seems to be) displaying AMS , hemiplegia. As pt. regains themselves take caution they may be used to coming to in weird places or they could be combative such as in drug use.

3. Really glad to know because any info for an unresponsive patient could be game changing.

New thoughts:

I never thought to put patient in a recovery position. Can this be done on a spineboarded pt by tilting it? Rather: should it? Nasal airway: we all know to keep things out of the mouth but with pt. seeming to breath okay should it be placed preemptively should condition change?

I cant wait for part 2 to get o2 sat, bloodsugar and physical assessment .

Well, I meant more that, whatever your method for ruling out C-spine injury (whether a specific protocol, “pain=collar,” or something more thoughtful), generally it always requires a conscious and reliable patient who can report pain and cooperate with a neuro exam. A post-ictal patient is not much help and we often end up assuming the worst unless a helpful bystander is like, “oh yeah, I saw the whole thing, and I instantly caught him in my huge arms and lowered him onto downy-soft memory foam.”

Regarding airways: the recovery position is a super handy thing that a lot of people seem to forget about in this business. (The same could be said for nasal airways.) Post-ictal patients sometimes manage their own airway okay, sometimes come around quickly enough that it doesn’t matter, and sometimes won’t tolerate being positioned just-so (they can have a mind of their own). Boards do cause all kinds of havoc with airways, and I have occasionally gone to great lengths to maintain the airway of an obtunded patient who I’m forced to lie flat (bilateral NPAs, suction, etc); you can indeed prop them at an angle if you strapped them adequately (of course, it’s always when we did a half-assed job that they later start to yak), or you can just try to be on the ball with suction and such. (Fortunately I’ve never had someone vomit while post-ictal, only while actively seizing.)

Hmm 10:30 in the morning at a grocery store probably isn’t your typical druggie lol but it takes all kinds.

Jump on the 2A and head to memorial? Maybe they’ll have muffins or fresh fruit in the EMS lounge!

I know we pilfered a Jefferson student ID but honestly even if they have past medical history there, if she’s a student she might appreciate not being at a learning hospital as a pt among her peers and proctors. Plus memorial is right there and… Muffins… It’s almost lunch time.