Location: SEMS HQ

Time: 18:42 Thursday

Conditions: Dusk; warm and clear

Equipment: fully stocked

Dispatch

The radio crackles… (click for audio)

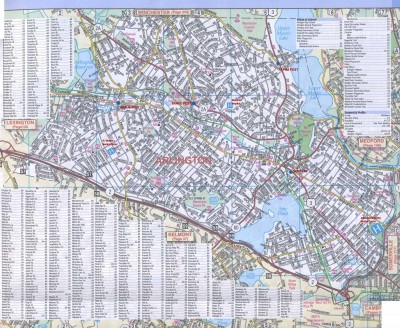

[Ambulance 61, respond priority 1 to Wadsworth Rd and Newport St for a man down. That’s A61, Wadsworth and Newport for the person spotted down in the street. Response with Engine 3. Time out 18:44. A61?]

Response

You respond with lights and sirens. As you pull down Wadsworth toward the intersection at Newport, Engine 3 is coming from the other direction, and you put yourselves on scene at the same time. Everyone slows down and starts chicken-necking, scanning the sidewalks for a body.

After a moment, you spot it; an adult male lying on his side, underneath an overhang, with his head upon a bundled jacket. Engine 3 parks at the curb and Steve wedges the ambulance into a gap, leaving just enough room for traffic to pass. Since you’re about ten feet from the patient, and you’re suspicious that you know what’s going on, you take the radio and leave the rest of the gear for now.

Scene

Donning gloves as you approach the patient, you see an older man dressed in numerous layers, generally dirty; a strong fruity odor greets you from several feet back. Checking the ground to make sure you don’t stick yourself on a needle, you come alongside and kneel.

Initial Assessment

You shake him briskly by the shoulder. “Hey!”

Grumbling, he rolls over. You see an alert but groggy male who easily localizes you. “Wha?”

“Hi. What’s up?”

His speech is slurred and sounds annoyed. “What do you want?”

“I’m Sam. What’s going on? You’re laying on the sidewalk.”

“I’m sleeping.”

“Are you feeling okay?”

“I’m fine!” he grunts.

“What’s your name?”

“… Richard.”

“Okay, Richard. Have you been drinking?”

There’s a pause, then he mutters, “Yeah!”

Behind you, a Scenarioville PD cruiser pulls up.

“How much have you had?”

“Couple beers.”

Finding one wrist hidden among numerous jackets, you palpate a radial pulse. His skin is warm and dry, and his pulse is strong, regular, and perhaps slightly rapid. You can’t see any obvious trauma, but there’s not much of him visible. His breathing seems unremarkable.

“Did you fall or anything, or are you just napping?”

“I’m just… I lay down.”

The SPD officer approaches. A firefighter informs him, “Drunk.”

“Any drugs today, Richard?”

“No, no.”

The officer is briskly patting him down as he struggles a little, slightly annoyed but not combative. He finds a flask-sized glass bottle of cheap vodka in one pocket, empty except for a swallow or two. A thick wallet comes out as well, and the officer flips it open. “Richard O’Connor. Scenarioville address.”

You peer closer to see his eyes. His pupils are equal and perhaps slightly larger than you’d expect for this time of evening. A sweet odor is strong on his breath, and he appears unwashed for at least the past few days.

“So is anything bothering you, or are you feeling okay?”

“I’m fine, go away.”

“Okay, Richard, the problem is that you’re sleeping on the sidewalk in a public area. Do you live around here?”

He shouts at you, “I live on the street!”

“All right. But again, we can’t have you here like this, okay? Someone’s going to ride a bike over you or something. Is there somewhere you can go?”

Unblinking, he stares at you. After a few seconds, you punt: “Let’s try and stand up at least.”

Together, three of you work to pull him to a seated position. He is mostly flaccid. Taking him by the hands, you’re able to pull him into a standing position with substantial effort, but he is limp and totally uncoordinated, unable to stand on his own. You lower him back to the ground, where he immediately rolls back onto his pillow, content.

“Okay, Richard, okay.” You give a head-nod to Steve, who walks back to your truck and pulls out the stretcher. “We can’t have you falling over in the street like this. We’re going to bring you to the hospital, all right?”

He grunts. Pulling the stretcher alongside and lowering it, you again perform a heavily-assisted pull to standing and help Richard turn and sit-fall onto the stretcher, pull his feet up, and throw a blanket over him before buckling the straps. You load him up into the ambulance and pile in.

“Can you snag some vitals?” you ask Steve. He sits at the patient’s right and starts trying to pull an arm free for a blood pressure. On the other side, you clean off a finger and perform a finger-stick. The blood glucose comes back as 82.

“108 over palp,” Steve tells you; he was able to get the outermost jacket off, “thinning” the arm enough for a cuff to get traction, but couldn’t pull up the remaining sleeves enough to put his scope onto the AC. “Pulse 98.” He jots those down for you.

“Okay, let’s go. St. Vincent’s.” He heads up front. You ask Richard to squeeze your hand and flex and extend his feet against resistance, briefly palpate his abdomen and pat him down for obvious trauma; you find nothing exciting. Checking the wallet, you jot down his name and date-of-birth. “Is anything else going on, Richard? Is this a normal amount for you to drink?”

“Yeah.” He seems to be falling asleep again.

“Do you have any medical problems?”

“Um… no.”

“Taking any medications?”

“No.”

“Are you allergic to anything?”

“No.”

Grabbing the radio, you make this report (click for audio):

[Evening, St. Vincent, Scenarioville Ambulance 61. We’re four minutes out with a 37-year-old male, found down on the sidewalk. EtOH, no drugs or trauma, he’s sleepy but doing fine. Any questions?]

“No, we’ll be waiting,” they reply.

You arrive and have Richard scoot into a hallway bed at the ED. A somewhat harried-looking nurse takes a quick report (click for audio) as you put the rails up and settle the blanket over him.

[So this is Richard; he’s 37. Someone called because he was napping on the sidewalk down by the highway. Says he had a couple beers; we found one of those 200-ml bottles of vodka on him, empty. Denies any drugs, no trauma, say he just lay down. Vitals are good, sugar is 84. Very sleepy. Denies any medical history, says this is pretty typical for him.]

She nods. “We know him well.” Dragging over a vitals monitor, she starts helping him pull off coats. “What are you doing, Richard? You know you can’t sleep there.”

You pat him on the shin and say good-bye; he waves at you absent-mindedly. You wash your hands, pick up a demographics sheet from registration, and head outside, where Steve has just finished wiping everything down and airing out the odor from the back. Clearing up over the radio, dispatch sends you to post at headquarters. You have some dinner in the fridge that’s starting to sound pretty good.

Discussion

Diagnosis: alcohol intoxication

A vanilla drunk call. Bystanders or motorists often notice people asleep by the road and call 911 to check on them; occasionally they are sick, so you should be prepared for anything including a cardiac arrest, but most often they’re drunk and passed out. A blood sugar is always wise, since hypo- and hyperglycemics can look drunk, and drunks are often hypoglycemic as well; we should also look for trauma, because drunks often fall. Beyond that, it’s mostly a matter of ensuring that there’s not some other problem masquerading as alcohol. Once that’s done, if the ABCs are adequate, they’ll just get a ride to the hospital to sleep it off. Services differ on how they handle borderline cases, but anyone who can’t walk, talk, or do much except fall asleep on the sidewalk certainly can’t remain there; in a few progressive systems you may be able to transport to a homeless shelter or another appropriate destination, but for most of us, they go to the ED.

It is unlikely that a chronic alcoholic like this would have no medical history at all, but it’s probably also unlikely that you’ll get much out of him. If he were sick, it would be smart to try and transport him to a facility that has his records.

I guess I’ll be the first to start commenting on these, since I like trying to figure it out as we go instead of getting it all at once.

So far, my list of likely diagnoses includes ETOH and/or hyperglycemia, as that odor could indicate either, and both are reasonable possibilities given the overall scene.

The first thing I want to do is get a better gauge of his mental status. Is he alert and oriented to person, place, and time? If not, how “with it” is he? Am I going to get more information or not?

If he’s not A&Ox3, he’s definitely going, but I’d still like to get any history I can first, especially about any alcohol or drug use. I’d also like to get a BGL to rule out hyperglycemia (or identify hyperglycemia if that is contributing to the problem. I’d also like to get a set of vitals.

If we do discover hyperglycemia, I’d like to take him to the closest appropriate facility, which seems to be St. Vincent’s based on our current location at Wadsworth and Newport. In that case, I’d push strongly for it even if he doesn’t want to go, including a consult with medical control if necessary. Ultimately, it’s his decision (if he’s A&Ox3 and can understand the risks and benefits of refusing treatment), but I’m going to work to try to convince him.

If he’s just sleeping and fine, or sleeping off his alcohol but still “with it” (A&Ox3 at a minimum, plus I’d prefer he be ambulatory), and just wants to sign off, I’m not going to argue too much.

If he isn’t A&Ox3 and/or can’t understand the possible consequences of not going to the hospital, he doesn’t get a choice, and I’m going to request PD to help. In fact, why don’t I have PD on scene already? Where I’m from they get dispatched automatically to all “unknown problem” or “man down” calls. If they aren’t already on the way I’d like them to start coming now.

Great points! These are, of course, pretty common situations in most areas, and how to handle it appropriately but with a scintilla of common sense can be tricky. There’s a fair amount of local culture to it as well; for instance, in many places police are very fond of “ya go with them or ya come with us.”

In any case, an update has been added; does it change your thinking at all?

(PD was in the middle of a high-priority coffee break, I expect.)

I’m definitely relieved to have PD on scene now, just in case he becomes belligerent.

I’m going to preface this by saying that I’m not used to dealing with these exact situations. I work mostly with a college-aged patient population, so I’m adapting what I’ve used and seen done with drunk college students.

I’d also, as mentioned before, like to get a better picture of his mental status. Is he “with it” and able to understand what’s going on, or is he unable to give “informed” consent? At least where I work, the official policy is A&Ox3, GCS 15 at a minimum, but they also need to be able to understand the risks of refusing treatment. It’s a bit of a grey area, since I don’t like “forcing” people to go to the hospital, because I do believe that people are entitled to make poor decisions if they wish, but on the other hand I don’t want something bad to happen to someone because they made a bad decision when they were “out of it”.

I definitely want to try to get more history from him if I can, although I doubt he’ll be able to give me much useful information. I could easily see him having medical conditions he isn’t aware of, so maybe I’d start with asking him when he’d last seen a doctor and go from there.

I still want a BGL just to rule out the possibility of hyperglycemia (or hypo, although I doubt it given his presentation).

Since he isn’t able to hold himself up or walk on his own, I’d like to try to convince him to go with us, although I doubt it’ll be easy.

With your protocols in mind then… if a patient must be alert and oriented to refuse transport, here’s a Zen koan purely regarding those definitions: is this gentleman alert?

He’s alert, but whether or not he’s oriented is a bit of a grey area. He’s answering questions, but somewhat sluggishly. He also never really gave us a good response to one question and seemed a bit confused by it. I’d call him alert but confused, or alert and oriented x1 or x2 depending on how he answers questions. The problem with A&O (and why I really hate it for calls like this) is that all it tells you is whether he can answer 3 questions or not: his name, where we are, and what day it is. It doesn’t really give us any good insight into his mental status. Whether or not we’d let him sign off is probably going to be a judgement call on the part of the individual provider; usually what we end up doing in these cases (since we only provide first-response, not transport) is to wait for the ambulance and let it be their decision instead of ours.

In this case, since I’d rather just make a decision and not give only vague answers, I’m going to decide that he’s “alert enough” for the purposes of the scenario to make a decision, and, provided that he can understand and articulate back to me the risks of refusing transport, I’d let him sign off after attempting to convince him otherwise. If the BGL comes back abnormal, that’s just another tool I can use to convince him to go with me.

What do you think?

I think you hit the important point — in this case, and honestly in most cases, the idea of “alert and oriented” is a painfully thin description of mental status. When I document I tend to avoid it and simply describe their behavior in words; this call might get “… easily roused, generally oriented but confused, slow to respond, and poorly conversational with slurred speech and profound ataxia. He repeatedly lapses back into unconsciousness without ongoing stimulus…” etc etc.

As far as definitions, though, while someone who’s appropriately sleeping in his bed and is easily woken would count as alert, someone who’s “sleeping” outside on the ground and keeps falling back asleep mid-conversation is not; that’s the textbook image of a person who responds only to stimulus. So more like the “V” of AVPU, although obviously no option conveys the situation very fully. Imagine finding a person unconscious after ejection through a windshield; you wouldn’t let them slide as “merely sleeping” in the middle of the road!

In most places I’ve worked it would not be considered acceptable to let someone like this remain in their own care. Partly this is a “public good” issue, because it’s an eyesore, and that can raise some difficult dilemmas, but in a patient like this it’s more clear; he’s not in a particularly safe situation and doesn’t same capable of establishing one on his own. Not that the ED is a particularly good place for him either, but we’re usually pretty limited in options. (Could he remain in his college dorm room in the care of friends, were that possible? A very different question.)

Apparently, we’ve hit the depth limit for replies.

Yeah, looking back on it, he’s definitely, as you suggested, more like a V on AVPU (GCS of 3/4/6?). The more I think about it, the less comfortable I’d be leaving him alone.

I guess I was thinking more in terms of the sign-offs I’ve seen here, but most of those that were questionable did have friends there to watch them. Then again, I’ve also definitely seen the local ALS ambulance do some really sketchy (as in, I’m pretty sure they were either violating state protocol or coming really close) RMAs.

The “SPD” Doesn’t stand for Scenarioville Police Dept”? Cause they were on the scene

Sure were!