Location: Bravo post

Time: 13:50 Tuesday

Conditions: Warm and clear

Equipment: fully stocked

Dispatch

“Small fries… and uh…”

You’re standing in line at Le Superior Burgery, your usual lunch place while you’re stuck at Bravo — the Pluto Post — when suddenly the radio on your shoulder crackles…

[Ambulance 61, respond priority 1 to 100 Grove St. 100 Grove St, the Wellington Park volleyball courts, for a 21-year-old male, conscious and breathing, altered mental status. 100 Grove is between Dudley St and Mass Ave. Response with Engine 3. A61?]

Response

“Never mind, we gotta go,” you tell the cashier, then come about and head out the door.

“I told you,” Steve says. “They saw us go in. Dispatch is watching our figure.”

“Yeah, well, I could probably cut down on the burgers anyway.”

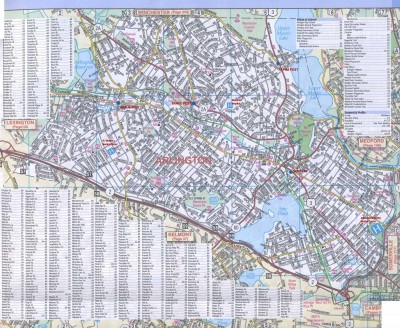

You cut over to Mass Ave and roll over toward the park. It’s not far, but Engine 3 is coming from even closer, so you notice them parked by the volleyball courts as you roll on scene. Wellington Park is a small but cute plot of land with volleyball, tennis, a playground, and a pretty nice field. You park by the engine, and a police cruiser pulls up behind you as you’re getting out.

A firefighter waves you down from the volleyball court. It’s spitting distance, and nobody looks dead, so you just grab the first-in and oxygen and waltz over there. “Let’s see what’s up,” you tell Steve.

Scene

There’s a small group of men, looking in their 20s, all loitering around the court looking sweaty. It’s paved, not sand, so you hardly see the appeal of volleyball — seems like a good way to take the skin off your knees — but nobody asked you.

As you approach, one of the firefighters fills you in.”This is Jim, started getting shaky while he was playing, now he’s confused, acting strange.”

You nod, set down your bags, and kneel.

Initial Assessment

You see a male, probably around 20, appearing healthy and well-built. He’s seated on a bench, upright but slumped, and he’s profusely diaphoretic; sweat is staining his armpits and chest, and beading up across his face. Everybody’s sweaty, of course, but he takes first prize; he also appears pale. He doesn’t look up as you kneel beside him.

Taking his wrist in a gloved hand, you feel cool, wet skin. His radial pulse is a little weak, but racing along, probably 100-130. He’s breathing okay, without obvious labor, although a little fast.

“Hi there,” you say. “I’m Sam.”

After a few moments, he looks toward you sluggishly.

“What’s going on?” you prompt him.

“Nothing,” he mumbles.

“Okay, what’s your name?” you ask.

The man doesn’t answer. “How are you feeling?” you prod.

“I’m…” he trails off vacantly. Awesome.

“Are you guys with him?” you ask a couple of the young bucks standing nearby.

“Yes sir.”

“What happened?”

“We were just playing volleyball… pretty good match, it’s a league thing, semifinal round. Going pretty hard, then he asked for a break, and he hasn’t gotten up from that bench since. He’s acting really weird, sort of antsy and drunk.”

“Was he having any problems before? Complaining about anything, acting ‘off,’ anything?”

“No, he seemed okay… definitely seemed like he was getting worn out, but we’re all going pretty hard here. It’s a league match.”

Aside to Steve, you say: “Can you grab a sugar?”

To the bystander: “So what’s his name?”

“Uh, Steve.”

Well, that won’t get confusing. “Does Steve have any medical problems you know about?”

“Oh, I don’t know… he had a bad knee for a while…”

One of the others chimes in. “He’s got diabetes, doesn’t he?”

“He does? I didn’t know that.”

You try not to roll your eyes, and return your attention to Steve the Patient. “Steve!” you call loudly, sticking your head in his face. He looks at you.

“Steve! Hello!”

“I’m Steve,” he mumbles.

You’re rescued from this exciting exchange of wits when a small beep sounds from Steve the Partner’s hands. He holds up the glucometer so you can see: 52 mg/dl.

“Hey, look at that,” you remark. Steve the Partner retrieves the BP cuff and starts playing with an arm while you turn back to the volleyball gang.

“Okay, it looks like his blood sugar’s a little low. Do you know if he’s eaten at all?”

“Haven’t seen him eat anything… he’s been drinking water, that’s it. He came from home though, so I don’t know.”

“Does he take insulin?”

Shrugs all around.

“Do you know if he has family or anything around here? Just someone we can contact?”

One of them digs up his phone and starts tapping at it. “Actually, yeah, I know his sister. Hang on a second.”

His buddy turns to stare at him. “How do you know his sister?” No answer. Tap tap tap.

The fire department is standing around, looking bored. The cop seems to have excused himself when you had your back turned; his cruiser is gone. You turn back to the Steves.

Your partner is deflating a cuff — “152/90… pulse about 110.” He slips his scope around his neck and raises an eyebrow, as if to say — now what?

“We’ll BLS it,” you tell him.

“Glucose?” he asks.

“Yeah… well… actually…” you turn to the jocks. “Do you guys have some Gatorade or anything? Something with sugar?”

“Yeah, totally.” One of them starts to hand you a half-empty sports drink. “Actually, wait… here’s a fresh one.”

He finds you an unopened bottle. Taking it and cracking the top, you kneel in front of Steve (the Patient).

“Steve? I have some Gatorade here, I want you to drink this, okay? Just take this bottle and drink.”

He hesitates for a moment, but takes the bottle. With some urging, he brings it to his lips and takes a small sip.

“Beautiful. Keep going, keep drinking.”

Behind you, one of the jocks says: “Hey, do you want to talk to his sister?”

Nodding at Steve (the Partner) to keep at the Gatorade duty, you turn and take the offered cell phone.

“Hello?”

“Hi, this is Samantha, Steve’s sister?”

“Hi Samantha, this is Sam from the ambulance. We’re here with your brother — can I ask you, is he diabetic?”

“Yes, yes he is.”

“Okay, that’s what we figured. His blood sugar is a little bit low, he was getting a bit confused and shaky playing volleyball. He’s drinking some Gatorade now.”

“Oh, good, thank you. He’s usually very good with his insulin, but sometimes he gets low.”

“Does he have any other medical problems?”

“No, he’s healthy, he’s in really good shape.”

“Any medications aside from the insulin?”

“I don’t… uh… he takes a pill also, something for the diabetes.”

“Metformin? Glipizide?”

“I’m not sure, I’m sorry.”

“No problem. Any allergies you know about? To any medications or the like?”

“He’s allergic to cats… I think that’s it.”

“Okay, great. Which hospital does he use?”

“His doctor is with University… he’s been there a couple times when his sugar dropped.”

“Can I just have his full name and his date of birth?”

“It’s Steve Proctor… P-r-o-c-t-o-r… and it’s… let’s see… May 9… uh, he’s 21 now… so… 1992?”

“Thank you. I think we’re probably going to bring him over to University, okay?”

“Okay, thank you very much.”

You close the phone and hand it back. Turning to the Steves, you see that he’s made it through half the bottle. It may be your imagination, but he seems to be looking a little better. Still, you’re disinclined to sit around titrating oral glucose until he’s coherent enough to sign off on a refusal.

“Steve, we’re going to bring you over to the hospital, okay? University Hospital, we’ll take you over and they’ll help you out. Your blood sugar is low and we need to get it back to normal.”

He looks back at you and seems to nod.

With your partner’s help, you both take an arm and help him to his feet. He walks like a drunk, but does walk with help, and you navigate over to the truck. Steve-the-Partner drags out the stretcher, and you help your patient plop on top.

Once he’s packaged up and inside, you holler, “Jefferson! Easy 2!” and climb in. Steve shuts you in and starts rolling.

“Keep sipping, keep sipping,” you encourage your patient. He’s getting toward the bottom of the bottle. Palpating a quick pulse, he seems to be settling down a bit.

After bouncing down the road a while, you retrieve the glucometer. Unpeeling the band-aid on his finger, you try to milk out another drop of blood, but his leak has stopped, so you regretfully jab another finger with a lancet. “Ow!” he says. Hey, it speaks.

The meter beeps back: 63 mg/dl.

“Steve?” you call, gently shaking his shoulder. He looks at you.

“How are you feeling?”

“Okay,” he answers, somewhat muted but coherent.

“Yeah? Do you know where you are?”

“In… an ambulance?”

“That’s right.”

“What happened?”

“Your blood sugar dropped, bud. You gave you a little sugar, but you’re still low, so we’re bringing you over to University Hospital.”

“Oh. Uh… wow. Okay.”

“Listen…” you fish a tube of glucose out of the cabinet and hand it to him. “You should get a little more glucose, okay? Can you try and get some of this down? Just squeeze it between your cheek and your gum. I’m afraid it’s probably going to taste like… uh, not good. But do your best.”

“I have… some tablets. Can I use those?”

“Oh, sure, that’s fine.” He digs into his pockets, and fishes out some tablets in a blister pack.

While he starts gobbling those down, you fetch the radio, hail the hospital, and call in this patch (click for audio)…

[Jefferson, A61, we’re four minutes out with a 21-year-old male, diaphoretic and confused, initial sugar of 52, now 63 after some glucose, mental status improving. Any questions, concerns?]

“Are you ALS?” they crackle back.

“BLS unit, ma’am, Ambulance 61,” you reply.

“Okay, thank you, Jefferson out.”

You palpate another blood pressure as you’re pulling in, around 130/p.

Your partner pulls out the stretcher, and you roll into the ED and stop at the triage desk. The nurse looks up over glasses. “Whatcha got?”

“Hypoglycemic.”

“Ah, that’s right. Name?”

You give the demographics and wait while he digs up the record in the computer. “Okay, go ahead,” he says. You reply… (click for audio)

[All right, so Mr. Proctor was out playing volleyball, going pretty hard, they noticed him getting tired, shaky, confused, very sweaty, pale… we found him alert but very spacey, with a sugar of 52, he had a bottle of Gatorade, got him up to 63, he’s had a few glucose tablets since then, coming around pretty well. Still a little groggy, but he’s with it. Talked to his sister, sounds like no real history but diabetes, does take insulin, and an unspecified pill. Maybe he knows.]

“Metformin,” Steve says from his stretcher. “I take metformin.”

“Ah, thanks.”

The nurse taps away, then finally directs you to a hall bed. You head over there, match up the beds, and let Steve scoot himself over, which he does tolerably well.

Tossing a blanket over him, you smile. “Feeling better?”

“Yeah, thanks bro,” he replies. “Sorry for all the trouble.”

“Hey, no sweat. Take care of yourself, okay? One of these times it might not go so well. Your sugar bonks and you crash your car, nobody’s around, that’s not good.”

“I hear you.”

You shake his hand and head out. Steve’s smoking in front of a “No Smoking” sign outside.

“Steve and Steve. That’s going to be you pretty soon if you keep eating the way you do.”

“I’m not living past 60 anyway,” he says on a cloud of smoke. “Sometimes you gotta say ‘fuck it.’ ”

Fair enough.

Discussion

Diagnosis: exercise-induced hypoglycemia

For diabetics, particularly those who take insulin (and to a lesser extent oral antidiabetics), maintaining a healthy blood sugar can be a difficult tightrope. The most common cause of hypoglycemia may be misdosing of insulin, but athletic exertion (either unexpected, above one’s baseline, or simply not adequately compensated-for by adjusting intake and medication) is just one potential cause. Additionally, the common symptoms of hypoglycemia — tachycardia, anxiety, diaphoresis, etc. — may resemble the results of exercise, making them difficult to recognize.

Severely altered or unresponsive patients who cannot manage their airway need ALS or the ED, where they’ll receive IV dextrose. But mildly hypoglycemic patients — in that window where they warrant treatment but can still take PO — can do well with any form of oral sugar. BLS units usually carry glucose gel, which works, but tends to be disgusting. Sugary drinks can work equally well and are often available.

Hypoglycemics are often treat-and-release cases, where patients wake up and refuse transport. This is always legally sketchy and sometimes medically so, since glucose-depleting factors (such as insulin) may outlast the short-acting glucose you’ve provided, and the patient may conk back out when you leave. Medical control is wise to invoke, in many areas ALS is required, and in some cases even ALS is not permitted to leave these patients. Be careful.

My only concern with this is helping pt. take fluids. Id be worried about pt. aspirating his own vomit. Id probably administer O2, ready suctioning, administer oral glucose and call for ALS intercept if reasonable. 4 minutes out seems wasteful.

A reasonable line of thinking!

Do you think it’s likely that a conscious, seated upright, talking (albeit confused) patient is going to vomit and aspirate?

Eh… it’s still a warm day and he’s been exercising. Many of the diabetic signs overlap with heat exhaustion. Id just be worried about secondary issues. I appreciate the reasoning given for helping pt. self administer gatorade but yeah, id be extra cautious about vomiting. But i am not nor have i ever been an emt.

I’m impressed your nurses knew what BLS was.

University Hospital — greatest in the world!

At least, the fictional world.

Within the fictional bounds of this city.

It’s ok to leave a pt like that w/o transport if you got BG up, got some one to get him something to eat with some carbs to keep BG up and you contact med control to discuss w/ Dr and get the go ahead to let pt refuse transport….. if stable of course.