Hand hygiene.

Wait, come back!

It’s not very exciting, which is one reason we don’t seem very impressed by it in EMS. Also, I have a theory that most prehospital providers (probably most people in general, with the possible exception of those who have taken a microbiology course and seen gross things) don’t really, on a visceral level, believe in germs.

Whatever the reason, we really drop the ball on this one. Walk into your nearest Mega-Lifegiving Medical Center, where the best and brightest are using the latest and greatest methods to save lives every day, and look at the hand sanitizer mounted to every wall. Look at the giant signs reminding everyone to clean their hands, cover their nose with their elbow, and lock themselves into an airtight bubble if they think they’ve got the flu. Watch nurses exit patient rooms wearing full-body gowns, eyeshields, respirators, and gloves. Then watch the ambulance crew wander in wearing week-old uniforms, touch everything, scoop up the patient like a sack of potatoes, heave him onto a suspiciously gray and drippy stretcher, and do just about everything but lick the doorknobs.

Admittedly, one difference between us is that the hospital makes its money in part based on metrics that include the number of nosocomial (healthcare-acquired) infections it sees. But maybe that’s a good thing. If our billing started depending on how many patients we infected, suddenly we might start believing in germs. Just a prediction.

Why should we care about universal precautions? For one thing, to stay alive. Not long ago I transferred a nurse between facilities. She was being admitted to a medical floor for a massive MRSA-colonized abscess on her cheek; it had been surgically incised and drained, and she was now beginning a course of antibiotics and further care. The cause? She’d idly scratched her face one day at work.

For some reason, I find this argument unconvincing to many of us EMTs and medics. I suspect that, as usual, we consider ourselves immortal. Whatever the case, if you find it compelling, go with it, but otherwise, try its mirror image: precautions keep your patients alive.

You may be a romping, stomping, deathless badass. You’re 18, you take your vitamins, and you’ve never been sick in your life. Staph tells stories about you to scare its children. But your patient is elderly, takes immuno-suppressant drugs, and has leukemia coming out of his ears. How’s his immune system? Do you want to find out?

He’s the reason that the hospitals have become so paranoid about cross-contamination — because this guy is right across the hall from a guy infected with Ultra-Virulent Pan-Resistant Skin Melting Brain Bleeding Disease, and it’s very, very easy for staff to touch one of them, then touch the other. Or touch the doorknob, which someone else touches, who then touches… etc. This is why hospitals are such dangerous places for sick people.

That’s why I’m not particularly paranoid about germs in my everyday life, but I try to bring a little paranoia to work with me. Because our patients may pass through many medical hands, but most of those hands are now climbing aboard the sanitation train. Yet the system is only as good as the weakest link, and especially when it comes to interfacility transfers, EMS may very well be that link. We wear the same uniform from patient to patient (if not from day to day), we don’t always replace linen or clean the stretcher, and equipment — never mind the ambulance itself — gets decontaminated far less often than after every call.

And perhaps, due to the nature of our work, some of this is necessary. We work in a more difficult and less controlled environment than the ICU, and maybe we can’t maintain exactly the same standards. (This argument is less convincing when it comes to non-emergent, routine transfer work, though — particularly when a patient’s infectious status is already known.) However, there are some things we can do that are easy, routine, and when introduced into our habits, create essentially no added work.

Number one is hand hygiene.

Whenever possible, I wash my hands after every call. It’s no burden. If I’ve delivered a patient to a hospital or other facility, I simply find the restroom (which I probably want anyway, because my bladder is the size of a grape) and wash. Many times a sink may even be available in the patient’s room.

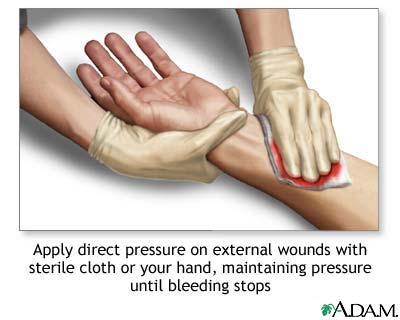

The proliferation of waterless hand sanitizers, usually alcohol-based foams or gels, has given us an alternative to this. When there aren’t any sinks, it’s the only way. But I don’t like ’em. They leave a residue that’s palpable, and which smells — and if you’re planning on eating anything, tastes — foul. They are also, in many cases, literally less effective. Although alcohol and similar agents kill most microorganisms, they don’t kill all of them (Clostridium difficile and the norovirus being notable exceptions), and like all contact sanitizers, they disinfect but do not clean. Any gross dirt, grease, or other contaminants on your hands (and this includes particles that are “macro”-sized but still too small to see) can cover or encase microbes, preventing antiseptics from reaching them. Unlike contact sanitizers, washing with soap and water is an essentially mechanical process: you are physically rinsing contaminants away from your skin and down the drain. (All that the soap does is “lubricate” hydrophobic particles to make them easier to rinse off.) Some soaps now are “antibacterial,” meaning they contain a germ-killing substance as well, but it’s not clear that these do any better of a job for routine purposes, and they may contribute to drug resistant strains. (They do, however, leave a microstatic coating on your hands afterwards, which helps to keep things clean a little longer.) Either way, most soap in healthcare facilities does contain an antimicrobial agent. In any case, I use the waterless sanitizers only when soap and water aren’t available.

Proper handwashing isn’t hard, but since it requires mechanically washing each portion of skin, it helps to have a system or you can easily miss spots. If you’re scrubbing in for surgery or a similar sterile procedure, you’ll need a much more stringent method than I use — but you’re not going to practice that ten times a day. So I use an approach that hits essentially the whole hand with as few steps as possible. Once you have the basic pieces in place, you can then do it fast for a routine wash, or spend much longer on each surface if you know that your hands are funky.

Here’s how I like to wash. It may seem elaborate or awkward at first, but with a little practice it’ll become second nature.

The same method can be used with waterless sanitizer. In the past, frequent washing tended to dry out your skin and lead to cracks (great windows for infection), but nowadays most soap in the hospitals contains moisturizer to prevent this.

A few points to remember:

- Washing is a mechanical process! Mere contact with soap doesn’t clean anything. If you didn’t rub an area of skin at least briefly, you didn’t clean it.

- Use warm water. Cold is a less effective solvent, and hot abuses your hands.

- If you’re also using the bathroom, consider washing before and after to avoid contaminating your… important areas.

- Drying with a towel is part of washing: it helps physically clean the hands, and wet hands are microbe-magnets.

- Although I don’t religiously practice the turn-off-the-water-with-the-towel technique, if you know that your hands were grossly contaminated, it’s a good idea; remember that whatever was on your hands before you washed is probably now on the knob.

- In an ideal world, we probably wouldn’t wear watches. In the real world, just try to be aware that it’s a great shelter for contaminants, and find a way to clean it (watch and band) regularly.

Recent Comments